Responsibility to the Future

It's a troubling sign of the modern political culture that being repeatedly and horrifically wrong about important subjects doesn't seem to make one less popular as an advisor. In fields where the subjects of professional analysis are granular and readily quantifiable, making crucial mistakes over and over again is a clear pathway to unemployment. Yet when the subjects are expansive and globally important, such as the politics of war or climate, repeated errors apparently aren't worth notice.

If these mistakes were simply signs of professional buffoonery, they'd be annoying but not worth comment. But these errors in analysis come from people with a great deal of influence over both policy-makers and semi-informed voters. Moreover, they focus on a subject that I follow closely: foresight.

In the era leading up to the current war in Iraq, the United States (as well as other nations) heard a cacophony of assertions about the inevitable results of the war. Some of these assertions were on-target; some were wildly (and tragically) off-base. Sadly, the voices that were most wrong still regularly appear on television news, on the editorial pages, and featured prominently in talk radio. The voices that were the most right, conversely, remain more-or-less invisible in the popular media.

So, following a blog trend, let me just say: What Digby (or, in this case, Tristero) Said.

It's high time that those who were right all along about Iraq have a significant national voice. [...] Whether or not [the high-profile pundits like William Kristol, Ken Pollack, and Tom Friedman] now recognize they were wrong, the fact is that they were when it counted most. Time to listen to those who got it right from the start.

I've written before about the responsibility that ethical futurists have to the future.

...the first duty of an ethical futurist is to act in the interests of the stakeholders yet to come -- those who would suffer harm in the future from choices made in the present. [...] Futurists, as those people who have chosen to become navigators for society -- responsible for watching the path ahead -- have a particular responsibility for safeguard that path, and to ensure that the people making strategic choices about actions and policies have the opportunity to do so wisely.

Implicit in this responsibility is the necessity of admission when one's analysis was wrong. But missing from this is the parallel admonition to the people and organizations that listen to foresight analysis: if your chosen "navigators for society" repeatedly run you into rocks, yet repeatedly deny having done so, you have a particular responsibility to stop listening to them.

You can't swing a dead cat-5 cable on the Interwebs today without running across a link to the "new Earth"

You can't swing a dead cat-5 cable on the Interwebs today without running across a link to the "new Earth"  (Or "I, for one, welcome our new cyber-mouse overlords!")

(Or "I, for one, welcome our new cyber-mouse overlords!")

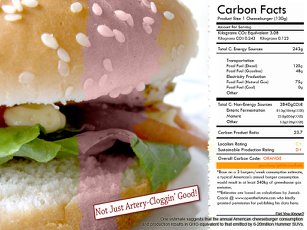

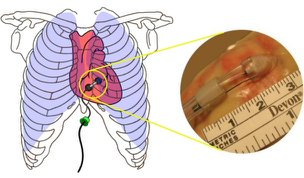

• CardioBot: The

• CardioBot: The

I wish that Nicolas Negroponte had never referred to it as the "one hundred dollar computer."

I wish that Nicolas Negroponte had never referred to it as the "one hundred dollar computer."

Trinity College Professor of Healthy Policy

Trinity College Professor of Healthy Policy