Let me tell you, being a cyborg isn't all it's cracked up to be. But it might be, sooner than you expect.

Let me tell you, being a cyborg isn't all it's cracked up to be. But it might be, sooner than you expect.

The popular image of a "cyborg" may be mash-up the character from Teen Titans and the Six Million Dollar Man (the balance of each depending upon how old you are), but the reality is not nearly so exciting. The truth is, we've had people with cybernetic prosthetics for quite some time, and the number is growing quickly. They're not action heroes (by and large), they're people all too often casually dismissed as "disabled."

But the demographics of the disabled are changing, as is the power of assistive technologies. And these changes have serious implications both for the role and visibility of the disabled in Western society and the ongoing debate between augmentation as "therapy" and augmentation as "enhancement."

I speak from personal experience on this one; I recently joined the ranks of the cyborgs. A few years ago, after noticing that my hearing seemed degraded, I saw an audiologist. His diagnosis wasn't encouraging: definite hearing loss, most likely congenital and almost certain to continue to degrade. At that point, it wasn't quite bad enough to require hearing aids. I went in for a new examination last month, and got the news: I really should be using hearing aids, at least if I wanted to stop annoying loved ones, friends and colleagues with my incessant "excuse me?" and "I'm sorry..." requests for repetition. After a few fittings and follow-ups, I got my new hearing assistance devices this week, and I'm wearing them right now.

These aren't just dumb amplifiers; they're little digital signal processors, small enough to fit into the ear canal, and smart enough to know when to boost the input and when to leave it alone. They're programmable, too (sadly, not by the end-user -- programming requires an acoustic enclosure, not just a computer connection). And here's where therapeutic augmentation starts to fuzz into enhancement: one of the program modes I'm considering would give me far better than normal hearing, allowing me to pick up distant conversations like I was standing right there.

These aren't just dumb amplifiers; they're little digital signal processors, small enough to fit into the ear canal, and smart enough to know when to boost the input and when to leave it alone. They're programmable, too (sadly, not by the end-user -- programming requires an acoustic enclosure, not just a computer connection). And here's where therapeutic augmentation starts to fuzz into enhancement: one of the program modes I'm considering would give me far better than normal hearing, allowing me to pick up distant conversations like I was standing right there.

They're not without their drawbacks. They're somewhat uncomfortable -- not painful, but impossible to ignore. The quality of the sound I get through the devices will take some getting used to; the size of the speaker limits just how clear the sound can be, I'm told. And, as far as I can tell, the electronics in these things change very slowly, Moore's Law be damned. I think there's a generational issue here: up until recently, most people wearing hearing aids came from the pre-computer era, and expected to pay outrageous prices for technologies of a just-good-enough quality (especially medical technologies). As more Baby Boomers -- and those of us younger than the Boomers -- start to require augmentation technologies, the manufacturers will increasingly see demand for greater quality and faster improvement.

A few hearing aid companies are beginning to see the light. Oticon, for example, offers a model of hearing aid with built-in bluetooth to make mobile phone calls easier. They don't come cheap, though -- just about $3,000 per ear. The first hearing aid company to act like a computer industry player instead of a medical tech industry player will make millions from the aging-but-tech-savvy.

The transformation of augmentation technology from pure therapy to a mix of therapy and enhancement is more visible in other types of prosthetics, however. Both New Scientist and the New York Times had recent articles about the remarkable capabilities of new prosthetic technologies, with a particular focus on cutting-edge models of artificial legs. In New Scientist (subscription required), the focus is on digital prosthetics offering new ways to compensate for disabilities:

[MIT researcher Hugh] Herr, who has made it his life's work to design improved prosthetic legs, is being funded by the US Department of Veterans Affairs to work on a prosthetic ankle that returns more energy in each stride. Inside each prosthetic are battery-powered motors that do a similar job to muscles. Last week, he wore two of these brand-new ankles for the first time. "It was absolutely amazing," he says. "It's like hitting the moving walkway at the airport." People wearing the new prosthetic have been shown to expend 20 per cent less energy when walking than with a standard prosthetic, and Herr says their gait also looks completely natural.

(Note the mention of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The Iraq War has become a significant catalyst in the rapid improvement of prosthetic technologies. The vast improvements in battlefield medicine that allow far fewer casualties to die have correspondingly meant that far more casualties come back with significant disabilities, including limb loss. As of January, 500 soldiers had undergone major amputations, a rate double previous wars.)

The sports implications of these new prosthetics haven't gone without notice. As the New York Times describes, South African Oscar Pistorius runs fast enough on his unpowered carbon fiber artificial legs that he's in contention for the 2008 Olympics -- if the International Olympics Committee will let him in. The IOC fears that continued advances in prosthetic technology will lead to "disabled" runners beating the all-natural runners in the not too distant future. They're right to be concerned; the most compelling part of the New Scientist article had to be this brief section:

Herr mentions a 17-year-old girl who has decided to go ahead with an operation to amputate a damaged leg because, he says, she thinks a new prosthetic will give her more athletic ability than she has now. For his own part, Herr claims he would not swap his prosthetic legs for natural legs, even if he could. "Would you buy a computer system if you were told you couldn't upgrade it for 50 years?" he says.

Herr's comment is eerily similar to an observation I made about why implanted computer systems were unlikely. We've seen such remarkable change in computer technology is such a short time, it's hard to imagine wanting to remain stuck with a rapidly-obsolescing model. But in a world of augmentation, is the biological body just another dead-end technology?

Or, to make this more personal: I expect that, over the next decade, hearing aid technologies will have improved enough that most of the drawbacks will have been rectified, and I'll have access to hearing capabilities better than ever before; over that same time, we may see biomedical advances that can fix deficient hearing, restoring perfectly functional natural hearing. Augmentation for therapy slides inexorably into augmentation for enhancement. Should I give up my better-than-human hearing to go back to a "natural" state?

This changing perception of both disability and augmentation can be summed up in this amazing picture of Sarah Reinertsen, taken by Stephanie Diani for a Times article about prosthetic fashion (and I strongly encourage you to click through to the full-size picture). Her artificial leg has no pretense of biology, yet is clearly part of her. It's not simply a prop to help her live a just-good-enough life; it's an augmentation that will only get better as the months and years pass. I doubt she looks with envy at the women with two "normal" legs on the dance floor; I suspect we're not too far away from a time when those women will look with envy at her.

This changing perception of both disability and augmentation can be summed up in this amazing picture of Sarah Reinertsen, taken by Stephanie Diani for a Times article about prosthetic fashion (and I strongly encourage you to click through to the full-size picture). Her artificial leg has no pretense of biology, yet is clearly part of her. It's not simply a prop to help her live a just-good-enough life; it's an augmentation that will only get better as the months and years pass. I doubt she looks with envy at the women with two "normal" legs on the dance floor; I suspect we're not too far away from a time when those women will look with envy at her.

I'm in a cluster of Internet radio podcasts this week.

I'm in a cluster of Internet radio podcasts this week. R.U. Sirius invited me back to serve as co-host for his shows this last weekend, and two have now appeared as MP3s.

R.U. Sirius invited me back to serve as co-host for his shows this last weekend, and two have now appeared as MP3s.

After months of work, the Metaverse Roadmap Overview is now available for download;

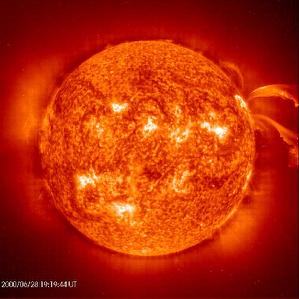

After months of work, the Metaverse Roadmap Overview is now available for download;  Summer Solstice: the longest day of the year!

Summer Solstice: the longest day of the year! Ethan Zuckerman

Ethan Zuckerman Doug Englebart

Doug Englebart Mike Liebhold

Mike Liebhold me

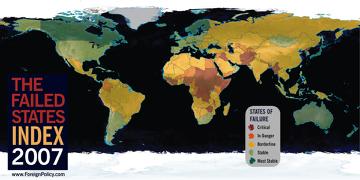

me Foreign Policy magazine has come out with its annual listing of "Failed States. Perhaps not surprisingly, most of the media attention to this list has

Foreign Policy magazine has come out with its annual listing of "Failed States. Perhaps not surprisingly, most of the media attention to this list has  Failure happens. Strategic plans that don't take into account the possibility of failure -- and propose pathways to adaptation or recovery -- are at best irresponsible, at worst immoral. The war in Iraq offers an obvious example, but the potential for failure in our attempts to confront global warming* may prove to be an even greater crisis. This is why I'm so adamant about the need to study the potential for

Failure happens. Strategic plans that don't take into account the possibility of failure -- and propose pathways to adaptation or recovery -- are at best irresponsible, at worst immoral. The war in Iraq offers an obvious example, but the potential for failure in our attempts to confront global warming* may prove to be an even greater crisis. This is why I'm so adamant about the need to study the potential for

Let me tell you, being a cyborg isn't all it's cracked up to be. But it might be, sooner than you expect.

Let me tell you, being a cyborg isn't all it's cracked up to be. But it might be, sooner than you expect. These aren't just dumb amplifiers; they're little digital signal processors, small enough to fit into the ear canal, and smart enough to know when to boost the input and when to leave it alone. They're programmable, too (sadly, not by the end-user -- programming requires an acoustic enclosure, not just a computer connection). And here's where therapeutic augmentation starts to fuzz into enhancement: one of the program modes I'm considering would give me far better than normal hearing, allowing me to pick up distant conversations like I was standing right there.

These aren't just dumb amplifiers; they're little digital signal processors, small enough to fit into the ear canal, and smart enough to know when to boost the input and when to leave it alone. They're programmable, too (sadly, not by the end-user -- programming requires an acoustic enclosure, not just a computer connection). And here's where therapeutic augmentation starts to fuzz into enhancement: one of the program modes I'm considering would give me far better than normal hearing, allowing me to pick up distant conversations like I was standing right there.

Woah. If this is confirmed, it's big.

Woah. If this is confirmed, it's big.

My month of travel is over, and I look forward to sleeping in my own bed.

My month of travel is over, and I look forward to sleeping in my own bed.