Happy New Year

Our world is small, fragile, and alone in the dark. All we have is each other.

Here's to building a future that's resilient, democratic, and open.

« November 2007 | Main Page | January 2008 »

Our world is small, fragile, and alone in the dark. All we have is each other.

Here's to building a future that's resilient, democratic, and open.

I am increasingly convinced that, whether we like it or not, geoengineering is going to become a leading arena of environmental research and development in the coming decade.

This is not because geoengineering -- the intentional large-scale manipulation of geophysical systems in order to change the climate and/or environment -- is the best way to deal with global warming. It's most decidedly not. The more we examine the initial proposals, in fact, the more we find that the risks outweigh the benefits. While we can't rule out a breakthrough discovery making this strategy safer, for now, its only environmental value appears to be as a desperate, last-ditch effort to head off catastrophe. Nonetheless, for many nations, this last-ditch possibility would be enough to warrant further research.

But as the observation at the top of the page suggests, geoengineering could be seen as having another kind of value: as a tool of international power.

When I wrote the above comments in March of 2007, it was in response to an observation by Dr. Ken Caldeira, a climate scientist who has gained recent attention for his discussions of geoengineering. In an interview with the Christian Science Monitor, he'd noted that uncoordinated work on intentionally altering the climate could lead to a "geoengineering arms race," with countries working on different -- and conflicting -- temperature and environment agendas. In such a situation, it seemed to me, great power nations could start to see geoengineering as another arena for competition. I elaborated a bit on the idea in October, when talking about the Politics of Geoengineering, citing the possibility of climate manipulation technologies being used as a tool of quiet warfare.

The more I think about this possibility, however, the more it seems like a disturbingly plausible scenario.

Rumors abound that the militaries and intelligence services of a variety of great power countries have, in the past, worked on dubious approaches to weather control. The idea of a geoengineering arms race may superficially parallel this line of thinking, but it's actually a very different concept. Unlike "weather warfare," geoengineering would be more subtle and long-term, and would have nothing to do with steering hurricanes or inducing local droughts; moreover, unlike weather control, we know it can work, since we've been unintentionally changing the climate for decades.

Geoengineering as a military strategy would appear to offer a variety of benefits. Research can be done out in the open, taking advantage of civilian work on anti-global warming geoengineering ideas. If my argument that nuclear weapons and open-source warfare have made conventional warfare essentially obsolete is correct, climate-based warfare would offer an alternative non-nuclear weapon, one that would be out of the reach of non-state actors. And the more we learn about how human activities alter the climate -- in order to alter those activities -- the more options might open up for intentionally harmful manipulation.

But wait: if global warming and climate disruption are, well, global, wouldn't "harmful manipulation" hurt the manipulating country, too?

Not necessarily -- or, at least, not to the same degree. The effects of global warming can vary dramatically, depending upon local geography and economy. Weather effects like hurricanes and heat waves depend on regional preconditions. The resilience of local technological and social infrastructures will also prove critical for determining how well regions handle climate disruption. For many of these reasons, many specialists worry that the regions hit the hardest by global warming will be in the developing world.

More importantly for this argument, it's for these reasons that some nations may believe that they can deal with global warming better than their competitors, or even benefit from it -- that, in the words of Vladimir Putin, it "wouldn't be so bad." Putin may have been joking, but a number of Russian scientists presenting at the 2003 World Climate Change Conference in Moscow seemed to make the same argument. Moreover, as this recent article in El Pais documents (English summary here, Google translation here), Russia's doing nothing to reduce its carbon emissions, and is instead building more coal-fired power plants; the only reason that it's in compliance with the Kyoto treaty is that its economy has declined relative to 1990. Given Putin's hardline propensities, if he thought that Russia would be harmed less than its competitors (or even benefit), would he be willing to reject the idea of taking advantage of that situation?

Lest I appear to be picking on Russia, one could make a similar argument for most great power leaders, if they saw the same opportunities. Much as Cold War nuclear strategists (parodied in Dr. Strangelove) could argue with a straight face about "winning" a nuclear war by having more survivors, advocates of a Global Warming War might see the US or Europe as better able to "ride out" a climate disaster than (say) China or the nations of the Middle East. It's awful to imagine, but that's why early nuclear strategists like Herman Kahn talked about "thinking the unthinkable."

In this scenario, even passive resistance to action against global warming could be seen as a mode of terraforming warfare.

How realistic is this idea? It depends. Given the high likelihood of further research into geoengineering projects for purely anti-global warming reasons, it seems almost certain to me that military or government officials in more than one country will come to similar conclusions about the technology's potential as a weapon. Actual weaponization of geoengineering methods would (one hopes) be slowed or stopped as more information comes in about unanticipated results of geoengineering tests, cost and/or efficiency, and the irrationality of believing that variations in the impact of climate disruption would be enough to alter balances of power.

One hopes. But it's hard to go wrong by assuming that someone in power is going to want to take advantage of a new way of "winning," no matter how difficult or irrational.

Welcome to the era of the Earth itself as a weapon.

(The following is an essay I wrote for the Center for Responsible Nanotechnology's December 2007 newsletter.)

How soon could molecular manufacturing (MM) arrive? It's an important question, and one that the Center for Responsible Nanotechnology takes seriously. In our recently released series of scenarios for the emergence of molecular manufacturing, we talk about MM appearing by late in the next decade; on the CRN main website, we describe MM as being plausible by as early as 2015. If you follow the broader conversation online and in the technical media about molecular manufacturing, however, you might argue that such timelines are quite aggressive, and not at all the consensus.

You'd be right.

CRN doesn't talk about the possible emergence of molecular manufacturing by 2015-2020 because we think that this timeline is necessarily the most realistic forecast. Instead, we use that timeline because the purpose of the Center for Responsible Nanotechnology is not prediction, but preparation.

While arguably not the most likely outcome, the emergence of molecular manufacturing by 2015 is entirely plausible. A variety of public projects underway today could, with the right results to current production dilemmas, conceivably bring about the first working nanofactory within a decade. Covert projects could do so as well, or even sooner, especially if they've been underway for some time.

CRN's leaders do not focus on how soon molecular manufacturing could emerge simply out of an affection for nifty technology, or as an aid to making investment decisions, or to be technology pundits. The CRN timeline has always been in the service of the larger goal of making useful preparations for (and devising effective responses to) the onset of molecular manufacturing, so as to avoid the worst possible outcomes such technology could unleash. We believe that the risks of undesirable results increase if molecular manufacturing emerges as a surprise, with leading nations (or companies, or NGOs) tempted to embrace their first-mover advantage economically, politically, or militarily.

Recognizing that this event could plausibly happen in the next decade -- even if the mainstream conclusion is that it's unlikely before 2025 or 2030 -- elicits what we consider to be an appropriate sense of urgency regarding the need to be prepared. Facing a world of molecular manufacturing without adequate forethought is a far, far worse outcome than developing plans and policies for a slow-to-arrive event.

There's a larger issue at work here, too, particularly in regards to the scenario project. The further out we push the discussion of the likely arrival of molecular manufacturing, the more difficult it becomes to make any kind of useful observations about the political, environmental, economic, social and especially technological context in which MM could occur. It's much more likely that the world of 2020 will have conditions familiar to those of us in 2007 or 2008 than will the world of 2030 or 2040.

Barring what Nassim Nicholas Taleb calls "Black Swans" (radical, transformative surprise developments that are extremely difficult to predict), we can have a reasonable image of the kinds of drivers the people of a decade hence might face. The same simply cannot be said for a world of 20 or 30 years down the road -- there are too many variables and possible surprises. Devising scenarios that operate in the more conservative timeframe would actually reduce their value as planning and preparation tools.

Again, this comes down to wanting to prepare for an outcome known to be almost certain in the long term, and impossible to rule out in the near term.

CRN's Director of Research Communities Jessica Margolin noted in conversation that this is a familiar concept for those of us who live in earthquake country. We know, in the San Francisco region, that the Hayward Fault is near-certain to unleash a major (7+) earthquake sometime this century. Even though the mainstream geophysicists' view is that such a quake may not be likely to hit for another couple of decades, it could happen tomorrow. Because of this, there are public programs to educate people on what to have on hand, and wise residents of the region have stocked up accordingly.

While Bay Area residents go about our lives assuming that the emergency bottled water and the batteries we have stored will expire unused, we know that if that assumption is wrong we'll be extremely relieved to have planned ahead.

The same is true for the work of the Center for Responsible Nanotechnology. It may well be that molecular manufacturing remains 20 or 30 years off and that the preparations we make now will eventually "expire." But if it happens sooner -- if it happens "tomorrow," figuratively speaking -- we'll be very glad we started preparing early.

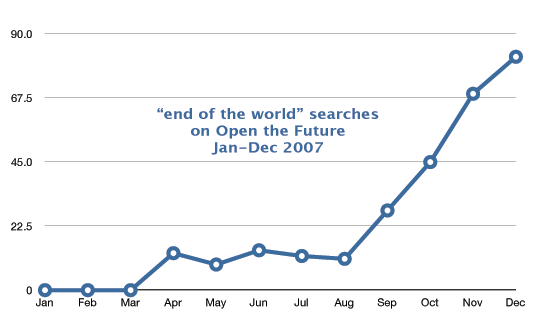

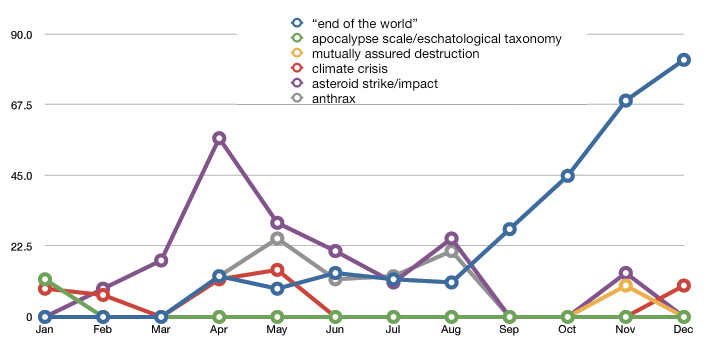

Taking a quick scan through my logs, I noticed something odd. Like many blogs, much of my traffic comes from people searching for particular terms. Normally, the searches that lead OtF are for topics I've written about (geoengineering, metaverse, etc.) or specifically about OtF/me. But over the past couple of months, one phrase in particular has leapt up the charts:

"End of the world" has moved from an occasional search subject early in the year to one of my top search terms.

It's even more dramatic when compared to other searches for potentially-related concepts:

As you can see, an initial bit of attention about last year's Eschatological Taxonomy died out quickly, and searches for subjects like being hit by asteroids and climate disaster vary without any real pattern. (Update: also note that, while my overall traffic has increased slightly over the year, the increase for "end of the world" is significantly disproportionate.)

This is a distant, early warning of something. I don't know what, but it probably isn't good.

The smart environment era is just about upon us, and I'm looking forward to seeing what happens when our previously "dumb" surroundings become embedded with Internet-connected intelligence. This is a subject I've followed for awhile, so I have some basic expectations as to what we'll see. Rapid adoption for social networks? Check. Greater energy efficiency? Check. Making the invisible, visible, in order to understand the subtle flows of information that support our lives? Esoteric, but check.

The smart environment era is just about upon us, and I'm looking forward to seeing what happens when our previously "dumb" surroundings become embedded with Internet-connected intelligence. This is a subject I've followed for awhile, so I have some basic expectations as to what we'll see. Rapid adoption for social networks? Check. Greater energy efficiency? Check. Making the invisible, visible, in order to understand the subtle flows of information that support our lives? Esoteric, but check.

Malware? Sadly, double-check.

Spam. Viruses. Phishing. "Zombie" computers. Our online lives take place amidst a massive, escalating, and inescapable battle between malware creators and system defenders. The Internet is an incredibly hostile place, full of malicious software designed to grab our attention, invade our privacy, and (occasionally) even steal our money. Fortunately, the Internet is made livable (and even enjoyable) due to the ongoing efforts of security specialists, and that ongoing battle happens rarely grabs our attention. We know this, and while we're not happy about it, we've learned to live with it.

For the most part, malicious bits of code and data -- collectively referred to as "malware" -- have remained comfortably limited to devices that we recognize as being (to a greater or lesser extent) computers. But as products and materials that have long been seen as non-computers start to get connected to the Internet, start to include processing capability and memory, start to offer "always on" wireless connections -- all in all, start to be active parts of our environments -- the likelihood increases that we'll start to see malware pop up in unexpected locations.

What kinds of products and materials? Cars, refrigerators, walls, clothing, highways, windows, televisions, product packaging... not to mention the various devices made solely to offer a cuddly, friendly interface for Internet messages. As processors and network hardware get smaller and cheaper, the more reasons we'll think of for wanting to put them in our stuff -- and the more platforms we'll create for malware.

Most of this will be spam. Spam infests every networked communication medium, and will likely to continue to do so for the various networked communication systems in development. It's ubiquitous in massively-multiplayer games, and I expect it to be a lingering problem as the Metaverse expands. Although we haven't seen it yet, I wouldn't be surprised if spam became a drag on the fast deployment of augmented reality type systems. While filters can work reasonably well, they're not universally available -- for example, I'm baffled as to why mobile phone carriers all haven't implemented basic filters on text message systems, given the rising volume of text spam.

Since the goal of (most) spam is to grab attention, my guess is that the first public outcry about material malware will be triggered by ads for increased member size, lottery winnings, or offshore casinos popping up on refrigerator doors, in-car displays, and digital picture frames.

Arguably, viruses (and trojans) have the potential to be a more serious problem, but they face more significant roadblocks. In the abstract, the best defense against widespread virus propagation is a "polyculture" model of systems, where no one "species" of host dominates. Viruses thrive in monocultures, whether industrial single-species forests or commercial single-operating system networks. In monocultures, all potential hosts for a virus have effectively identical structures (whether DNA or OS), and the "disease" can easily jump from host to host. In polycultures, conversely, viruses can't propagate as readily since new potential hosts often have widely-divergent configurations.

Anti-virus code, firewalls and the like will certainly help, but hardware and software diversity may be the most important factor preventing the rapid spread of viruses in the smart environment world. The more closely the operating system in your smart shirt is related to the operating system in your television, your Internet-connected camera, and/or your smart home energy system, the more likely it is that someone will be able to figure out how to write something that could infect all of them.

A greater concern is that the viruses (and trojans) that do exist will take advantage of the legacy of trust we have for the dumb versions of the now-smart materials; will we have to worry about what the (voice-controlled) refrigerator overhears or the (video-chat-ready) television sees?

I'm particularly fascinated by the possible new forms of malware that could emerge unique to the new technologies. I've mentioned some possibilities in the past: intentional misinformation/data-pollution in information-dense environments; physical "spam" produced by Internet-connected fabricators; even "sock bots," scripted avatars used to disrupt virtual world gatherings while looking like a mass activity (upon reflection, "bot mob" is probably a better term). The more powerful and flexible our everyday tools and environment become, the more we'll have to pay attention to keeping them on our side.

Does this mean that we're diving headlong into disaster? No. Just as we've become inured to the inundations of spam, accustomed to regularly updating anti-virus software, and bored with the constant, clumsy phishing come-ons, we'll eventually be resistant (both technically and culturally) to the malware outbreaks that pop up in our new toys. The transition period may be a bit rough, but if we're aware of the potential before it hits, we won't be so readily taken by surprise.

Just make sure you keep your anti-virus/spam-filter/malware filters on your furniture up to date.

Although I tend to focus on social impacts in my discussions of the participatory panopticon, and the related Metaverse concepts of augmented reality and lifelogging, I'm not immune to the siren song of gadgets. If I'm going to argue that technology and culture co-evolve, I shouldn't focus entirely on only one side of that pairing. That said, I don't do the full-on gadget geek thing very often, but it's the end of the year, and I'm going to indulge.

Although I tend to focus on social impacts in my discussions of the participatory panopticon, and the related Metaverse concepts of augmented reality and lifelogging, I'm not immune to the siren song of gadgets. If I'm going to argue that technology and culture co-evolve, I shouldn't focus entirely on only one side of that pairing. That said, I don't do the full-on gadget geek thing very often, but it's the end of the year, and I'm going to indulge.

It's not just an academic subject for me, of course. As I noted in May, I have a Nokia N800 Internet tablet, a Linux-based device that offers full computery goodness in a platform a bit bigger than a mobile phone. I'm no stranger to the field -- I still have my first-generation Newton. But as the picture to the right suggests, my menagerie of touch-screen toys has recently expanded.

Pocket Internet tablets represent a digital niche that has yet to reach its full potential. None of the current devices are anywhere close to perfect. But as the wireless Internet becomes more pervasive -- in terms of both its presence in our lives and its presence in the air around us -- the more that we'll start to depend on mobile tools to give us rich access to our networks and data. By checking out these tablets, I'm not just satisfying my gadget urges, I'm beta testing one scenario of the future. At least, that's my justification.

Let me note that none of these devices are phones. My misgivings about the iPhone have not abated (that's an iPod Touch in the photo), and the alternatives I've considered all have serious failings. For now, pairing a dedicated Internet tablet with a 3G phone gives me the greatest flexibility. Since May, that's meant the N800, and I've been fairly happy with it. But after doing a short bit of casual consulting for Nokia, they generously offered to send me a new N810, the follow-up to the N800.

It arrived yesterday. Hit the extended entry for some gadgetry observations:

N810:

Overall: I'll probably move to the N810 for my pocket wifi use, but I currently don't see the justification for the ~$200 premium over the N800.

I also picked up an iPod Touch (iPT) yesterday, partly out of irritation at some of the design choices for the N810, partly out of curiosity, and partly because I had a last-minute, unexpected gig that netted me enough to get a little treat.

The interface on the iPT just blows away that on the Nokia devices. The N800/N810 user interface sits in a middle ground between a desktop UI and a finger-top UI, completely satisfying neither. The Nokias are clearly more versatile and hackable (without having to downgrade firmware or the like), but the iPT is much more immediately usable. It's not just the big icons, it's little things like "kinetic scrolling," where a flick of the finger offers a bit of momentum to a scroll, or the way that a typed letter pops up to show you what you've actually hit.

The hardware isn't nearly so clearly in Apple's favor, however. The iPod Touch is much smaller than I thought -- the N810 is significantly fatter and has more surface area, although both are "pocketable" -- and while that's convenient, it does make the iPT feel a bit more fragile than the Nokias. The display on the iPT is crisp, but offers a much smaller overall area than the N800/N810 -- the Nokia screens are 800x400, and the iPT is less than half that. The accelerometer on the iPT is amusing, and the iPT defaults to a vertical mode that is more usable for a hand-held device in my experience than the horizontal-only mode of the N-series. The Nokias, conversely, offer expandable storage and swappable batteries.

It's in the connectivity arena that the N800/N810 shines. The iPT is a nice WiFi device, but that's its only means of connecting to the Internet. The N-series devices have bluetooth, meaning that they can tether to a bluetooth 2.5G/3G phone for Internet anywhere. That right there makes a big difference; as commonplace as WiFi is, it's still not as pervasive as cellular networks. Moreover, when the N-series device is plugged into your computer, the memory cards show up as mounted drives, for easy drag & drop file management. The N-series tablets use a normal file system, while the iPT requires all file connectivity to go through iTunes, and makes the file system on the device itself invisible to the user.

Mobile Safari is nice, but the fact that it can't do Flash and doesn't do Ajax (at least as far as I can tell) seems to have problems with some Ajax sites means that it's at a real disadvantage on the modern web. The Mozilla-based browser on the Nokia devices -- despite being occasionally unstable -- is far more broadly usable in my experience, and handles Ajax & Flash with ease. Google Maps work like Google Maps on the desktop, including grab & scroll. YouTube is the real YouTube, not a subset.

Overall, the iPT is more immediately useful than an N-series tablet, but is much shallower in terms of function. It is, after all, an iPod with a web add-on, rather than a web tablet that can play music. If the iPT could tether over bluetooth, it would be good enough that I'd probably end up using it over the N800/810; without that access, however, I will probably stick to the N810.

Last call for "Green Tomorrows."

Last call for "Green Tomorrows."

I'm looking forward to the chance to engage an audience with the ongoing evolution of my "sustainability success" scenarios. This web seminar will mix teleconferencing and webconferencing, and will rely on lessons that Gil Friend and Natural Logic have learned by using this system for much of this last year, and that I have learned undertaking a series of remote scenario workshops. I'll be doing a direct presentation for the first half, and a Q&A session for the second half.

Once again, here's the pertinent info:

Date: Thursday, December 20, 2007

Time: 10:00am - 11:00am

Location: http://www.natlogic.com/webinars. Preregistration required.

Street: Time shown is PST. 1pm EST, 12pm CST, 11am MST

Join futurist Jamais Cascio for a stimulating webinar -- you can attend from anywhere -- exploring how the sustainability revolution will transform our politics, our economics, and our lives.The process of building a sustainable future follows diverse paths, and the choices we embrace today will shape the future we encounter over the next 20 years. By adopting a scenario planning approach, Cascio will look at what kinds of results we might get, and what kinds of opportunities and surprises those results could have in store.

Another Carbon Neutral Learning™ opportunity from Natural Logic. Series Host: Gil Friend, CEO

(NOTE: This event requires preregistration.)

As you might suspect, this isn't a free show, although the price is reasonable (especially for people coming in as part of an organization -- the price is per line, not per listener, so callers are perfectly welcome to use a speakerphone and bring friends). Gil does these web seminars as part of Natural Logic's business, and I'm curious about how well the model links to my other projects. It's certainly a much greener way of doing a presentation -- no air travel required.

If you do get a chance to listen in, I'm really eager to get your feedback on both the presentation style and content. This is the working concept for a book -- is it something you'd want to read?

Hey there, folks out there in Internet-land -- do you find these "topsight" posts useful or interesting? I sometimes puzzle over whether the various individual entries would be better off as individual short posts, rather than as a catch-all post. The downside of that is my apparent inability to keep individual posts terse. The upside would be clearer topics and easier inbound links, should you find yourself wanting to point to a particular item.

Hey there, folks out there in Internet-land -- do you find these "topsight" posts useful or interesting? I sometimes puzzle over whether the various individual entries would be better off as individual short posts, rather than as a catch-all post. The downside of that is my apparent inability to keep individual posts terse. The upside would be clearer topics and easier inbound links, should you find yourself wanting to point to a particular item.

Opinions? Ideas? Bueller?

• Prototyping the Participatory Panopticon, Part 1: Waaaaaay back in the dark days of early 2006, I gave a little talk at the TED conference on the idea of an "Earth Witness" program, with sensing devices built into mobile phones to allow for collaborative environmental science. Nice talk, Al G liked it, but it wasn't flashy enough for the TED talk public listing. Anyway, the notion of an enviro-phone seemed possible but not necessarily plausible back then -- but now Nokia is running with the idea, and showcasing its "Eco Sensor" concept phone.

To help make you more aware of your health and local environmental conditions, the Nokia Eco Sensor Concept will include a separate, wearable sensing device with detectors that collect environment, health, and/or weather data.You will be able to choose which sensors you would like to have inside the sensing device, thereby customizing the device to your needs and desires. For example, you could use the device as a “personal trainee” if you were to choose a heart-rate monitor and motion detector (for measuring your walking pace).

Here are some other examples of customized sensing devices you could build:

Environmental monitoring

- Atmospheric gas-level monitor (including carbon monoxide, particulate matter, and ground-level ozone detectors, for example)

- Ultraviolet radiation sensor

- Subscription to environmental catastrophe warning and guidance system

Personal health

- Motion detector

- Heart rate monitor

- Noise level monitor

Weather monitoring

- Air pressure sensor

- Humidity sensor

- Temperature sensor

- Subscription to environmental catastrophe warning and guidance system

This isn't a phone that's being prepped for sale, it's a "hey look at how cool and green we are" design that won't make it out of the lab -- at least in this form. (Quick aside: we've had concept cars for awhile, and concept computer designs -- although rarely from the manufacturers. Now we have concept phones. What's next?) But like concept cars, the technologies deployed in this model can end up in shipping units a year or three down the road.

• Prototyping the Participatory Panopticon, Part II: When talking about the various technologies of the participatory panopticon, I usually make a point of mentioning that the "offloaded memory" functions of PP devices could be particularly appealing to aging populations. Seems I'm not the only one:

When Mrs. B was admitted to the hospital in March 2002, her doctors diagnosed limbic encephalitis, a brain infection that left her autobiographical memory in tatters. As a result, she can only recall around 2 percent of events that happened the previous week, and she often forgets who people are. But a simple device called SenseCam, a small digital camera developed by Microsoft Research, in Cambridge, U.K., dramatically improved her memory: she could recall 80 percent of events six weeks after they happened, according to the results of a recent study.

A wearable camera, the SenseCam takes a shot every 30 seconds, and makes the collected images available for later viewing. What I didn't expect -- and is a wonderful result -- is that by examining the recorded images, the user could move those digital memories to long-term brain memory.

Here's an important guideline for people thinking about technology futures: look at the needs the aging and disabled have yet to have filled. As the baby boom in the west hits retirement age -- and especially as the even larger demographic bulge in China moves to retiree status -- we'll see an explosion of demand for the kinds of technologies to help the active disabled and active elderly maintain personal and social flexibility.

In other words, this is just the beginning.

(Via MedGadget)

• Moving Down the Apocalypse Scale: One of the most-linked items I've ever posted here is my "eschatological taxonomy," a scale of different levels of apocalypse -- from regional destruction all the way through to the total elimination of the planet. Fun stuff.

Jason Matheny, at the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University, gives the notion of dealing with the end of the world a more thorough examination. In his "Reducing the Risk of Human Extinction," just published in the academic journal Risk Analysis, Matheny gives a detailed account of possible ways the human race (and its descendants) could end, and what we might be able to do about it. Most interesting for me was his discussion of "discounting," that is, how the value of future human lives varies from the value we place on present-day human life. It's a fairly deep philosophical question done up in economics drag.

Even if extinction events are improbable, the expected values of countermeasures could be large, as they include the value of all future lives. This introduces a discontinuity between the CEA of extinction and nonextinction risks. Even though the risk to any existing individual of dying in a car crash is much greater than the risk of dying in an asteroid impact, asteroids pose a much greater risk to the existence of future generations (we are not likely to crash all our cars at once) (Chapman, 2004 ). The "death-toll" of an extinction-level asteroid impact is the population of Earth, plus all the descendents of that population who would otherwise have existed if not for the impact. There is thus a discontinuity between risks that threaten 99% of humanity and those that threaten 100%.

This is a very interesting piece, and definitely adds to the ongoing conversation about how best to allocate scarce resources for resilience.

(Bonus! It turns out that Matheny is also involved with New Harvest, the leading organization working on the development of cruelty-free meat!)

• Oh, No Revisted: When it's not advertisers trying to beam audio messages into your skull, it's political campaign specialists trying to figure out how to manipulate your emotions. Campaigns & Elections magazine has an article entitled "Mind games: how campaigns of the future will play with your brain," looking at the various new technologies that could influence how political campaigns of tomorrow would be run.

Campaign ads that break through the filters could pack more punch, thanks to the nascent field of neuromarketing. The field is based on scientific research on what messages make the human brain light up in which areas--and what those lights mean. For instance, a campaign might look to craft a message that is sure to evoke a warm, fuzzy feeling about a candidate. Opponents might try to instill the opposite."It comes down to making sure that what is being said by the candidates or by the party has been crafted specifically to elicit particularly neurochemical responses," said Cascio, the San Francisco futurist. He envisions Democratic and Republican neuromarketing firms crafting dueling messages in the heat of a campaign.

(Uh, yeah, they quote me -- but also some other names you might recognize, including Zephyr Teachout, Jason Tester from IFTF, and David Brin.)

Of course, this all leads to the inevitable conclusion:

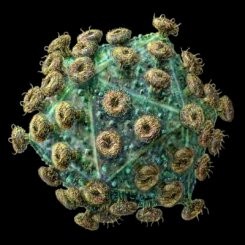

Word of the Week: Paleovirology: The study of "fossil" viruses living in our cells as endogenous retroviruses.

Word of the Week: Paleovirology: The study of "fossil" viruses living in our cells as endogenous retroviruses.

Endogenous retroviruses (ERVs), like the more typical retroviruses such as HIV, rewrite the DNA of the cells they infect; the endogenous retroviruses do so not just to the somatic (body) cells, but to the germline (reproductive) cells, becoming part of the DNA we pass down to the next generation. These aren't rare -- more of our DNA comprises these old retroviruses than genes that actually code for proteins. New ERVs generally will quickly lose their potency as viruses, but can come to play critical roles in how our bodies operate. ERVs, for example, protect a fetus from the mother's immune system in all placental animals; ERVs are also thought to be possible triggers for multiple sclerosis.

Paleovirology is interested in the non-coding ERVs, looking at how they might have first become introduced and examining their interactions with the body. A new article in the New Yorker explores the latest news from the field, including strong evidence that the study of paleovirology could lead to a treatment for HIV. It turns out that shortly after the hominid (us) line split from the hominoid (chimpanzee, bonobo, gorilla) line, the apes became infected with an ERV called PtERV; the proteins that the hominid line evolved that defended against PtERV had the side effect of making us vulnerable to HIV (which can infect apes, but doesn't make them sick).

To figure this stuff out, paleovirologists have a fun trick: they're able to resurrect extinct viruses to see what makes them tick by piecing together chunks from related species.

Then, last year, Thierry Heidmann brought one back to life. Combining the tools of genomics, virology, and evolutionary biology, he and his colleagues took a virus that had been extinct for hundreds of thousands of years, figured out how the broken parts were originally aligned, and then pieced them together. After resurrecting the virus, the team placed it in human cells and found that their creation did indeed insert itself into the DNA of those cells. They also mixed the virus with cells taken from hamsters and cats. It quickly infected them all, offering the first evidence that the broken parts could once again be made infectious.

(Fortunately, it's standard procedure in paleovirology to add code to prevent the newly-awakened retroviruses from reproducing more than once.)

Endogenous retroviruses have fascinated me ever since I read Greg Bear's Darwin's Radio, a 1999 novel about human evolution. The idea that viruses are critical in evolution is, on the surface, astonishing, but ERVs also have come to serve as a powerful metaphor for external agents changing not just how an organization or community functions now, but also how it operates in the future (and how new organizations and communities that get spun off operate). I'd be tempted to talk about this as a memetic endogenous retrovirus, but the acronym would be MERV, and that just opens itself up to too many jokes. Maybe "cognitive endogenous retrovirus -- CERV" would be better.

The Center for Responsible Nanotechnology today published eight scenarios exploring differing drivers for the advent of molecular manufacturing. This was the "virtual workshop" series I led earlier this year, and the scenarios reflect the work of over 50 people across six different countries. I wrote the initial drafts of five of the eight narratives.

The Center for Responsible Nanotechnology today published eight scenarios exploring differing drivers for the advent of molecular manufacturing. This was the "virtual workshop" series I led earlier this year, and the scenarios reflect the work of over 50 people across six different countries. I wrote the initial drafts of five of the eight narratives.

I'm particularly happy with a couple of them:

Thirty million dead from the Rot in the US. Today, everyone knows at least one person who had died a horrible death during the pandemic, and most of us know a lot more than that.As soon as it was clear that the Rot was showing up in cargo, collapse was unavoidable. All nations called a quarantine on goods shipped from China. China, suddenly losing its export dollars, called in trillions of dollars in debt from the USA. The US dollar crashed. The credit rating of the United States went through the floor.

If you think about the money, it makes it easier not to think about the corpses.

and

Refugees from ecological disaster zones, surging towards those countries seemingly less-affected by global warming, were met by armed force; nations hit by drought or agricultural collapse no longer regarded it as a temporary problem, and some grabbed the water supplies and farmland of weaker neighbors; those places still producing abundant levels of greenhouse gases came under verbal attack at the UN and in the global media, and the world was treated to the surreal spectacle of the United States (greatest per-capita greenhouse output) and China (greatest total greenhouse output) on the verge of coming to blows over which one was the worst carbon offender.Those tensions came to a boil in 2015 when coordinated acts of sabotage took nearly a hundred Chinese coal-fired power plants offline. The Chinese government blamed the U.S. and put its military on high alert; the American government responded in kind. Fortunately, before either side could launch a preemptive attack, a rural Chinese movement took credit for the sabotage. Beijing was taken by surprise when the resulting crackdown backfired, with some regiments refusing to attack Chinese citizens and others actively joining the movement. A smuggled camphone clip of renegade Chinese military aircraft bombing the nation's largest coal-fired power plant was the top-rated video on YouTube that year.

Believe it or not, both of these have happy endings.

My talk at the Stanford Metaverse Meetup on November 27 is now available as a video.

My talk at the Stanford Metaverse Meetup on November 27 is now available as a video.

Downloadable Quicktime (warning: big, big file)

The whole thing runs for nearly 90 minutes, including both the talk and the Q&A (there's also a 5 minute intro and another 5 minute commentary towards the end).

One thing that really leaps out at me while watching this: I simply can't stand still. I must have driven the cameraman crazy with my wandering back and forth, and I'd probably be absolutely unable to speak if you tied my hands to my sides. And don't get me started on the weird "jazz hands" moves I apparently can't stop myself from doing.

On the plus side, the sound quality's really good.

Let's see what's bubbled up through the Intertubes recently...

Let's see what's bubbled up through the Intertubes recently...

• Oh, No: In their never-ending quest to make ordinary citizens rise up and destroy capitalism, the advertising community has discovered a new place to put hard-to-ignore ads: in your skull.

New Yorker Alison Wilson was walking down Prince Street in SoHo last week when she heard a woman's voice right in her ear asking, "Who's there? Who's there?" She looked around to find no one in her immediate surroundings. Then the voice said, "It's not your imagination." [...]The billboard uses technology manufactured by Holosonic that transmits an "audio spotlight" from a rooftop speaker so that the sound is contained within your cranium.

Go ahead and scream. A local hero (or "vandal") stole the speaker out of the billboard shortly after it went up; the speaker has since been replaced (no word on whether they've added more security... hint hint). The Holosonic rep suggested that it might take time for people to become accustomed to this new technology. I suspect it will take less time for the system to become subject to some harsh regulation.

Please.

(Via Warren Ellis)

• Zzzzap: The New York Times reports on a study done by Massimiliano Vasile at the University of Glasgow on the best ways to deflect an asteroid heading towards the Earth. Nuclear bombs don't work, pushing with a spacecraft wouldn't work well, and "gravity tractors" would likely take far too long to be effective. Vasile determined that the best option is the swarm:

The best method, called “mirror bees,” entails sending a group of small satellites equipped with mirrors 30 to 100 feet wide into space to “swarm” around an asteroid and trail it, Vasile explains. The mirrors would be tilted to reflect sunlight onto the asteroid, vaporizing one spot and releasing a stream of gases that would slowly move it off course. Vasile says this method is especially appealing because it could be scaled easily: 25 to 5,000 satellites could be used, depending on the size of the rock.

The vaporized material then serves as a "rocket" to push the asteroid to a new course. If done early enough, this should be entirely achievable, with a large but not impossible price tag. The one problem (not addressed in the article) is that of liability: if an asteroid is heading towards the Earth, and is projected to hit (say) Egypt), and is nudged enough to change course but not enough to avoid impact -- now in (say) India -- who gets the bill? There would be horrific regional damage either way. Would nations with the power to do this avoid the undertaking out of fear of legal risks?

• Welcome to the Participatory Panopticon, Officer: A New York cop interrogated a teenager about a shooting, and tried to intimidate him into confessing. On the witness stand in court, however, the copy claimed to have done none of that. Is the jury going to believe the cop or the kid? How about the kid's MP3 recorder?

Perino had arrested Crespo on New Year's Eve 2005 while investigating the shooting of a man in an elevator. While in an interrogation room at a station house, Crespo, then 17, stealthily pressed the record button on the MP3 player, a Christmas gift, DeMarco said.

The impact of the Participatory Panopticon will not be felt the most in our privacy, but in our ability to get away with secrets and lies.

On December 20th, I'll be conducting something of an experiment.

On December 20th, I'll be conducting something of an experiment.

In coordination with Natural Logic, I'll be leading an hour-long "webinar"* on four different scenarios of how we may respond to global warming, and build a sustainable future. Here's the link, and the relevant info:

Join futurist Jamais Cascio for a stimulating exploration of how the sustainability revolution will transform our politics, our economics, and our lives.The process of building a sustainable future follows diverse paths, and the choices we embrace today will shape the future we encounter over the next 20 years. By adopting a scenario planning approach, Cascio will look at what kinds of results we might get, and what kinds of opportunities and surprises those results could have in store.

This webinar is part of the ongoing Carbon Neutral Learning™ program from Natural Logic, bring you engaging, practical, up-to-date guidance from leading practitioners. Series host: Gil Friend, Natural Logic CEO.

Date: Thursday December 20

Time: 1:00 pm ET (10:00am CT, 11:00am MT, 10:00am PT)

Length: 60 minutes

Price: $129

Oh, that. This is why it's an experiment. Gil Friend and Natural Logic have done webinars* on sustainability topics in the past, and they've worked well both as a way of providing information and as a business opportunity. I'm curious about how well the model would work for me.

Please pass along the info about this event to people and organizations you think might find this of value.

(*I really, really hate this term, but it now seems to be the accepted/required jargon. Ugh.)

The web is full of references to a Mahatma Gandhi quote:

First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.

This line gives solace to people working on obscure or seemingly hopeless endeavors, wondering if the entrenched incumbent systems will ever give way.

After reading Andrew Leonard's latest post to "How the World Works," about a ridiculous US Chamber of Commerce advertisement trying to scare people away from supporting a relatively mild carbon regulation (the Lieberman-Warner cap-and-trade bill) (PDF), however, it strikes me that the reverse is true for those entrenched incumbents.

For those in power unwilling to accept change, the pathway is:

First they fight you, then they laugh at you, then they ignore you, then you lose.

As Leonard's post demonstrates, as we work against the powers-that-be that seek to avoid any effort to head off climate disaster, we've now moved solidly into the second stage of this path.

Just a few updates for those of you who like to hear these things:

Just a few updates for those of you who like to hear these things:

My talk at the Metaverse Meetup the other night went splendidly, and the video should be available real soon now. For those of you who can't wait, the folks at Ugo Trade did a terrific job of capturing the content and the spirit of my talk -- not a transcription, but a thoughtful depiction.

The picture of me giving the talk was taken in Second Life by Lisa Rein. Thanks, Lisa!

The entire recording of my interview for Spark! on CBC radio is now available for downloading & listening. It actually holds together pretty well, and nicely covers (in a conversational way, not a lecture) many of what I think are the key issues surrounding the rise of the metaverse concept.

This past weekend's edition of, um, Weekend Edition included a story about the Singularity Summit (you remember, back in September... I guess this worked best as a filler story). Many of the notables show up in interview snippets, and I make a guest appearance, too. The odd thing is that it was at least a 30 minute conversation that ended up being cut down to two sentences. Welcome to radio.

Director of Impacts Analysis, Center for Responsible Nanotechnology

Fellow, Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies

Affiliate, Institute for the Future