Paleovirology

Word of the Week: Paleovirology: The study of "fossil" viruses living in our cells as endogenous retroviruses.

Word of the Week: Paleovirology: The study of "fossil" viruses living in our cells as endogenous retroviruses.

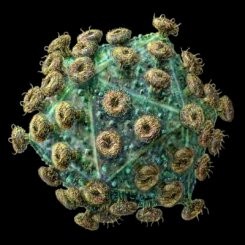

Endogenous retroviruses (ERVs), like the more typical retroviruses such as HIV, rewrite the DNA of the cells they infect; the endogenous retroviruses do so not just to the somatic (body) cells, but to the germline (reproductive) cells, becoming part of the DNA we pass down to the next generation. These aren't rare -- more of our DNA comprises these old retroviruses than genes that actually code for proteins. New ERVs generally will quickly lose their potency as viruses, but can come to play critical roles in how our bodies operate. ERVs, for example, protect a fetus from the mother's immune system in all placental animals; ERVs are also thought to be possible triggers for multiple sclerosis.

Paleovirology is interested in the non-coding ERVs, looking at how they might have first become introduced and examining their interactions with the body. A new article in the New Yorker explores the latest news from the field, including strong evidence that the study of paleovirology could lead to a treatment for HIV. It turns out that shortly after the hominid (us) line split from the hominoid (chimpanzee, bonobo, gorilla) line, the apes became infected with an ERV called PtERV; the proteins that the hominid line evolved that defended against PtERV had the side effect of making us vulnerable to HIV (which can infect apes, but doesn't make them sick).

To figure this stuff out, paleovirologists have a fun trick: they're able to resurrect extinct viruses to see what makes them tick by piecing together chunks from related species.

Then, last year, Thierry Heidmann brought one back to life. Combining the tools of genomics, virology, and evolutionary biology, he and his colleagues took a virus that had been extinct for hundreds of thousands of years, figured out how the broken parts were originally aligned, and then pieced them together. After resurrecting the virus, the team placed it in human cells and found that their creation did indeed insert itself into the DNA of those cells. They also mixed the virus with cells taken from hamsters and cats. It quickly infected them all, offering the first evidence that the broken parts could once again be made infectious.

(Fortunately, it's standard procedure in paleovirology to add code to prevent the newly-awakened retroviruses from reproducing more than once.)

Endogenous retroviruses have fascinated me ever since I read Greg Bear's Darwin's Radio, a 1999 novel about human evolution. The idea that viruses are critical in evolution is, on the surface, astonishing, but ERVs also have come to serve as a powerful metaphor for external agents changing not just how an organization or community functions now, but also how it operates in the future (and how new organizations and communities that get spun off operate). I'd be tempted to talk about this as a memetic endogenous retrovirus, but the acronym would be MERV, and that just opens itself up to too many jokes. Maybe "cognitive endogenous retrovirus -- CERV" would be better.

Comments

I find myself fascinated by your fascination with endogenous retroviruses. Your blog introduces me to the details of stuff I'd never even heard of --

Posted by: Siel | December 14, 2007 2:08 PM

Resurrecting extinct virii is about >this

Posted by: Howard Berkey | December 16, 2007 7:18 PM

Fascinating. This seems to confirm much of the work done by Lynn Margulis on symbiosis. It also seems to wed us to this planet - we're symbiotes, and it would be pretty damned hard to replicate that in space colonies.

Posted by: David Foley | December 17, 2007 6:23 AM