Long-Run vs. Long-Lag

All distant problems are not created equally.

By definition, distant (long-term) problems are those that show their real impact at some point in the not-near future; arbitrarily, we can say five or more years, but many of them won't have significant effects for decades. Our habit, and the institutions we've built, tend to look at long-term problems as more-or-less identical: Something big will happen later. For the most part, we simply wait until the long-term becomes the near-term before we act.

This practice can be effective for some distant problems: Let's call them "long-run problems." With a long-run problem, a solution can be applied any time between now and when the problem manifests; the "solution window," if you will, is open up to the moment of the problem. While the costs will vary, it's possible for a solution applied at any time to work. It doesn't hurt to plan ahead, but taking action now instead of waiting until the problem looms closer isn't necessarily the best strategy. Sometimes, the environment changes enough that the problem is moot; sometimes, a new solution (costing much less) becomes available. By and large, long-run problems can be addressed with common-sense solutions.

Here's a simple example of a long-run problem: You're driving a car in a straight line, and the map indicates a cliff in the distance. You can change direction now, or you can change direction as the cliff looms, and either way you avoid the cliff. If you know that there's a turn-off ahead, you may keep driving towards the cliff until you get to your preferred exit.

The practice of waiting until the long-term becomes the near-term is less effective, however, for the other kind of distant problem: Let's call them "long-lag problems." With long-lag problems, there's a significant distance between cause and effect, for both the problem and any attempted solution. The available time to head-off the problem doesn't stretch from now until when the problem manifests; the "solution window" may be considerably briefer. Such problems can be harder to comprehend, since the connection between cause and effect may be subtle, or the lag time simply too enormous. Common-sense answers won't likely work.

A simple, generic example of a long-lag problem is difficult to construct, since we don't tend to recognize them in our day-to-day lives. Events that may have been set in motion years ago can simply seem like accidents or coincidences, or even assigned a false proximate trigger in order for them to "make sense."

But a real-world example of a long-lag problem should make the concept clear.

Global warming is, for me, the canonical example of a long-lag problem, as geophysical systems don't operate on human cause-and-effect time frames. Because of atmospheric and ocean heat cycles (the "thermal inertia" I keep going on about), we're now facing the climate impacts of carbon pumped into the atmosphere decades ago. Similarly, if we were to stop emitting any greenhouse gases right this very second, we'd still see another two to three decades of warming, with all of the corresponding problems. If we're still three degrees below a climate disaster point, but have another two degrees of warming left because of thermal inertia regardless of what we do, we can't wait until we've increased to just below three degrees to act. If we do, we're hosed.

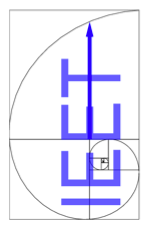

With long-lag problems, you simply can't wait until the problem is imminent before you act. You have to act long in advance in order to solve the problem. In other words, the solution window closes long before the problem hits.

We have a number of institutions, from government to religions to community organizations, with the potential to deal with long-run problems. We may not do well with them individually, but as a civilization, we've developed decent tools. However, we don't have many -- perhaps any -- institutions with the inherent potential to deal with long-lag problems. Moreover, too many people think all long-term problems are long-run problems.

(This argument emerged from a mailing list discussion of the Copenhagen Consensus. Smart people, with lots of good ideas, but clearly convinced that we can address global warming as a long-run problem.)

Sadly, recognizing the difference between long-run and long-lag problems simply isn't a common (or common-sense) way of thinking about the world. We evolved to engage in near-term foresight (and I mean that literally; look at the work of University of Washington neuroscientist William Calvin for details), and (as noted) we have developed institutions to engage in long-run foresight. Long-lag is a hard problem because it combines the insight requirements of long-run foresight (e.g., being able to make a reasonable projection for long-range issues) with the limited-knowledge-action requirements of near-term foresight (e.g., being able to act decisively and effectively before all information about a problem has been settled). Both are already difficult tasks; in combination, they can seem overwhelming.

A salient characteristic of long-lag problems is that they're often not amenable to brief, intense interactions as solutions. Dealing with such problems can take a long period, during which time it may be unclear whether the problem has been solved. Politically, this can be a dangerous time -- the investment of money, time and expertise has already happened, but nothing yet can be shown for it.

Another long-lag problem that shows this dilemma clearly is the risk of asteroid impact. It turns out that nuking the rock (as in Armageddon) doesn't work, but a small, steady force on the rock for a period of years, years ahead of the potential impact, does. Pushing the rock moves the point of impact slowly, and it may take a decade or more before we can be certain that the asteroid will now miss us. That's why the slim possibility of a 2036 impact of 99942 Apophis frightens many asteroid watchers: if we don't get a good read on the trajectory of the rock long before its near-approach in 2029, we simply won't have time to make a big enough change to its path to avoid disaster.

But tell people in power that we need to be worrying now about something that won't even potentially hurt us until 2036, and the best you'll get is a blank look.

My interest, at this point, is to try to identify other long-lag problems, and to see what kinds of general conditions separate long-run and long-lag problems. With both global warming and asteroid impacts, the lag comes from physics; with peak oil (and other resource collapse problems), conversely, the lag comes from the need for wholesale infrastructure replacement. What else is out there?

Comments

Well, at least with Apophis we're not talking an extinction event; it would suck mightily (worse than Krakatoa by far) but it's nowhere near big enough to wipe out even a small continent.

Still, scary; it's going to be passing inside the geostationary satellites.

Strangely enough, it's also small enough that nuking it would work just fine.

But early deflection would be better of course. It just has to be nudged to miss a 600m target.

Posted by: Howard Berkey | October 3, 2008 7:46 AM

For a more mundane example, you might use as an example controlling a train. Like the tragic accident in LA recently: no doubt both engineers saw the other train coming at them, but by the time they did it was much too late for either to avert a collision.

Posted by: Kevin D. Keck | October 3, 2008 8:25 PM

There are a few large inertia problems that come to mind. The first, in a week where the US ran up $700 billion dollars on its bar tab, is unfunded future fiscal problems, such as US social security commitments. In this case the problem is pretty well understood, and because no-one is serious about fixing it, there is a default solution that people are willing to slide towards - renege, either explicitly by not paying out, or more sneakily by printing money and therefore reducing the worth of the commitment by inflation.

Another related problem is demographic change. There are some ranters like Mark Steyn who worry about ethnic rates of population replacement in the rich world, but most of the rich world has it easy compared to places like Estonia and China. This is talked about but not really addressed because there's no good consensus on solutions (save dropping the one-child policy).

Lastly I'm no civil engineer but I vaguely recall some structural maintenance problems are like this, if you don't fix the dam / bridge well ahead of time its vastly harder, more expensive, and more likely to fail.

In fact, aren't a lot of the key setting elements in Superstruct long-lag?

Posted by: Adam Burke | October 4, 2008 1:45 AM

I'd argue that, in our time and for the foreseeable future, most non-trivial long-term problems are long-lag problems. Solving them requires the fundamental tasks of learning and retooling our mental models - and that takes a long time, especially since we evolved cognitive abilities best suited to the short run.

Posted by: David Foley | October 5, 2008 1:43 PM