Resilience and the Next Disaster

If you live in the San Francisco Bay Area, have friends or loved ones who do, or simply enjoy the various products and services to be found around these parts, take heed:

When the Big One hits, it won't be pretty.

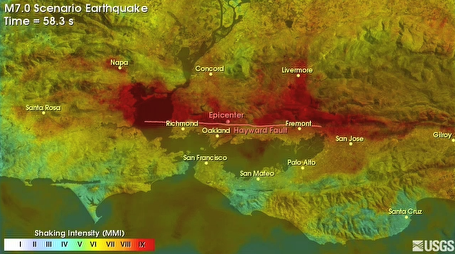

The US Geological Survey has put out a set of videos showing the shaking associated with a major earthquake on the Hayward Fault. There hasn't been a big one on the Hayward Fault in over 300 years, and it's overdue for a serious seismic event. The USGS videos cover quakes measuring 6.8, 7.0, and 7.2, with epicenters ranging from Fremont in the south to the San Pablo Bay in the north.

Short version: if you live in the Berkeley hills... well, it's not pretty. No place is truly safe -- Santa Cruz seems to come out okay -- but some places are likely to be flattened, regardless of the precise epicenter. (It's worth noting that the location of the epicenter does not correlate to the worst damage -- in fact, a quake hitting at the Fremont location is actually worse for more of the East Bay than one centered in Oakland.)

So what do you do to prepare? There are numerous good sources for earthquake advice and kits, but (as is my habit) I want to look at the broader picture.

Survival in an earthquake, generally speaking, requires much of the same kind of practices as survival in a hurricane, in a terrorist attack, or any other form of shocking hit with long repercussions. It all comes down to resilience.

Here are my key elements of a diverse system -- I'll explore each in more depth in the coming days (as my schedule permits):

Diversity: Not relying on a single kind of solution means not suffering from a single point of failure. (Prepare for different kinds of problems -- needing to escape the house, needing to stay in the house, dealing with no water, etc.)

Redundancy: Backup, backup, backup. Never leave yourself with just one path of escape or rescue. (Make sure you have multiple copies of critical documents and extra amounts of key medications.)

Decentralization: Again with the single point of failure problem. Centralized systems look strong, but when they fail, they fail catastrophically. (Don't store your emergency supplies in one location -- spread them out.)

Collaboration: We're all in this together. (Take advantage of -- and learn to use -- collaborative technologies, especially those offering shared communication and information.)

Transparency: Don't hide your systems -- transparency makes it easier to figure out where a problem may lie. (Make sure key shut-off switches -- for gas, especially -- are readily identified.)

Openness: Many eyes make all bugs shallow. Share your plans and preparations, and listen when people point out flaws. (You're safer in an emergency when everyone is safer.)

Fail Gracefully: Failure happens, so make sure that failure states don't make things worse than they are already. (Think about what'll happen when disaster strikes -- what will fall, shatter, burst into flames, and what can you do now to prevent it?)

Flexibility: Be ready to change your plans when they're not working the way you expect. Don't get locked in to a particular approach. (Pay attention to what's happening around you, and don't expect things to remain stable.)

Foresight: You can't predict the future, but you can hear its footsteps approaching. Think and prepare. (Make sure you have your emergency kit ready before the emergency hits.)

Resilience, people. That's how we deal with a chaotic world.

Comments

Great post. I wonder what resilience mapping like this, done across the whole country on multiple spectra (weather disasters, earthquakes, etc) would reveal?

Posted by: Alex | October 15, 2008 7:31 PM

Those videos are a lot more alarming when you're tired and don't notice the motion is exaggerated by three orders of magnitude for effect.

Still, damn.

Posted by: Howard Berkey | October 18, 2008 12:31 AM

>So what do you do to prepare?

Move to a more stable part of the country?

People are starting to question why we spend so much money building stuff in hurricane zones on beaches. Why aren't we questioning the logic of putting one of our major economic engines in a nasty seismic zone?

Posted by: jet | October 18, 2008 6:15 PM

Move to a more stable part of the country?

Now would that be somewhere in the New Madrid Fault Zone in the midwest, where the building regulations are such that even a 6.0 would likely kill tens of thousands?

There is no safe place. Earthquakes pose a risk, but so do tornados, and hurricanes, and massive drought, and terror, and...

The people talking about hurricane zones & beaches, at least what I've seen, are talking about either *re*building in locations already (and repeatedly) flattened by storms/floods, or building in locations very likely to be hit by global warming-induced sea level rise.

To me, it makes a lot more sense to look for ways of becoming more resilient and secure than to try (in vain) to find someplace that'll never have a disaster.

Posted by: Jamais Cascio |

October 19, 2008 3:19 PM

|

October 19, 2008 3:19 PM

Yeah, New Madrid had four of the largest quakes in continental history; wabash had a 7.5 or two as well.

Then there's the yellowstone caldera.

Plus, the entire interior and most of the east coast is one fossil fuel crisis away from widespread deaths from exposure; you guys have *serious winter* there.

Then again, I am hardly one to listen to. I moved from the second most seismically risky urban area in the world to the most risky one. Estimated foot traffic density during post-event exodus from a catastrophic Kanto region quake is six people per square meter; that's 44 million people walking out on the remaining surface streets of an area roughly the size of the Bay area.

Posted by: Howard Berkey | October 20, 2008 4:08 AM