Memorial Day (repost)

(Originally posted on Memorial Day, 2006)

Andrew Jackson Wickline, my grandfather, the man I was named for, died [six] years ago, shortly before Memorial Day; a veteran of World War II, he was given a military service on Memorial Day itself, 2003.

Andrew Jackson Wickline, my grandfather, the man I was named for, died [six] years ago, shortly before Memorial Day; a veteran of World War II, he was given a military service on Memorial Day itself, 2003.

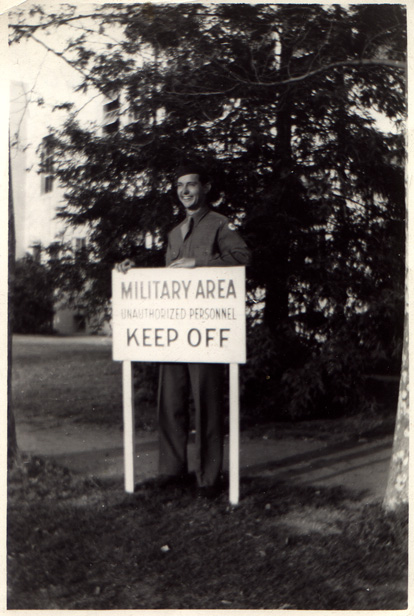

A short while before he died, Grandpa Jack gave me a box of old photos from the war. Over 500 pictures, taken by the company chaplain for the 80th Field Hospital, and offered to the men afterwards; Jack was one of very few who took copies of the pictures. I've scanned a small handful of them, and put them up on the web, but I really need to scan them all.

The photos are yellowed and clearly showing their age, but they are intact. Will the same be said in sixty years for the pictures we take today? My hard drive is full of images, taken by all manner of digital cameras -- but few have been printed out, and while I have multiple backups, digital media is inherently ephemeral. Formats change; people get sloppy. I have disks with essays from graduate school in formats that I can no longer read. How long until I can no longer read the image files found on some old CD I burned years ago?

Physical objects are not permanent, and I couldn't share the photos from the middle of the last century so easily without converting them first to digital form. I know the value and power of electronic media. I simply wonder how much of our future's past will be lost when locked into long-discarded formats and devices.

It is especially incumbent upon those of us who think about the future to remember what has gone before. The future doesn't just happen; events don't emerge fully-formed, like Athena from Zeus' head. The world in which we live is the result of myriad victories and mistakes, chances taken and decisions regretted, paths followed and options ignored, people loved and people forgotten. Too often, we pay attention solely to prominent names, the leaders and celebrities, and give them credit for creating the present. Artifacts like a box of old photos from a long-ago war remind us of how today's world was truly shaped, and the roles that everyday people played in making it come about.

I look at the people in my grandfather's photos, and wonder: did they know they were remaking the world? Were these simply snapshots to them, vacation photos with an edge, or did they recognize that they were documenting their roles in a monumental political transformation? How would our understanding of the second world war differ if everyone had carried a camera, not just one person out of hundreds, or thousands?

I look at the people in my grandfather's photos, and wonder: did they know they were remaking the world? Were these simply snapshots to them, vacation photos with an edge, or did they recognize that they were documenting their roles in a monumental political transformation? How would our understanding of the second world war differ if everyone had carried a camera, not just one person out of hundreds, or thousands?

Under Mars, a site archiving soldiers' photos from the present Iraq War, gives us a hint. For some soldiers, the pictures are simply snapshots, a way to hang onto a moment with friends. For others, they are historical records, filtered not through the eyes of a journalist or through the official accounts, but anchored to their own perspective, their fear and elation and wonder and horror. These are the artifacts of a citizens' history of the world -- if we can remember how to view them.

Memories are imperfect, and photos -- digital or physical -- have an aura of authority, but are no less subjective. But in the gathering of myriad subjective stories and images, a collaborative truth emerges. The more memories that get added to this collection, the more powerful the truth; beware histories that are written solely by victorious leaders.

My grandfather, Andrew Jackson Wickline, gave me many gifts over the years, but this box of photos is an incredible legacy. Every time I look at them, I sense their gravity and power. I don't know what I'll do with them -- I'm very happy to listen to suggestions -- but I do know that I'll treasure them. They're tangible evidence that history comprises the lives of all of us, not just the great and the famous, and that all of our actions help to shape the world to come.

Comments

Jamais-

It is quite a dilemma, the preservation of this soft of information. Probably, photographs are the best medium we will come up with for a VERY long time. They are readable directly, which is a huge -- and largely unacknowledged -- benefit. Any other digitized media will become unreadable if it's particular support infrastructure becomes extinct.

Perhaps the best way to attain resilience of information is in the way that genes and religions have done: Don't worry about perfect replication, but instead make lots of different types of copies that can respond to any situation that comes up. Witness how many plants are capable of synthesizing wintergreen fragrance, or how many animals are capable of sequestering calcium in their bones. The genetic information for performing these feats is just as fragile and susceptible to forgetting as your photos, but because it is replicated in everything from birches to ferns, and elephants to shrews, the likelihood of this happening is next to nothing.

Similarly, religions like Christianity and Islam which have flexibility to incorporate local customs and holy days (dia de los muertos in mexico, all souls day in Europe) have allowed them to spread and preserve their fundamental information, while other similarly fervent early religions have been utterly forgotten.

I'd say, your best bet for resilience is to make as many different kinds of copies as you can, and try to imbue each of those copies with the same emotional weight that made you write this blog post about a bunch of somebody else's memories :)

I suppose you could say that sympathetic grandkids are the best storage media of all.

-@dmuren

Posted by: Dominic Muren | May 25, 2009 5:50 PM

For much of our history only a few people have had access to the means of representing and controlling the construction of history. It's only with the emergence of printing and photography that many more of us now have access to the means of re-presenting our lives. What of the way we use the digital medium and computers? We organise our words here, we store our information here, and in a way our words and images become lost in this space. But this doesn't need to be the end of the story. With the development of printing on demand (POD) we all have the potential to contribute to a lasting document of our everyday lives - producing our own books. A history that we can share with our children, and they with their children.

But we need to get away from this generalised thinking and begin to to develop some deep thinking about how we can specifically contribute to making history, we need to encourage people to become involved, to participate in this social history, to see themselves in a variety of contexts, and it needs people to encourage, orchestrate, and choreograph this activity. This activity might contribute to how we see ourselves, through the lenses of histories.

Posted by: Tony Hall | May 26, 2009 1:47 AM

Maybe you can speak to www.shorpy.com - they do something like this.

Posted by: Dibyo | June 22, 2009 7:19 AM