Magna Cortica

One of the projects I worked on for the Institute for the Future's 2014 Ten-Year Forecast was Magna Cortica, a proposal to create an overarching set of ethical guidelines and design principles to shape the ways in which we develop and deploy the technologies of brain enhancement over the coming years. The forecast seemed to strike a nerve for many people -- a combination of the topic and the surprisingly evocative name, I suspect. Alexis Madrigal at The Atlantic Monthly wrote a very good piece on the Ten-Year Forecast, focusing on Magna Cortica, and Popular Science subsequently picked up on the story. I thought I'd expand a bit on the idea here, pulling in some of the material I used for the TYF talk.

One of the projects I worked on for the Institute for the Future's 2014 Ten-Year Forecast was Magna Cortica, a proposal to create an overarching set of ethical guidelines and design principles to shape the ways in which we develop and deploy the technologies of brain enhancement over the coming years. The forecast seemed to strike a nerve for many people -- a combination of the topic and the surprisingly evocative name, I suspect. Alexis Madrigal at The Atlantic Monthly wrote a very good piece on the Ten-Year Forecast, focusing on Magna Cortica, and Popular Science subsequently picked up on the story. I thought I'd expand a bit on the idea here, pulling in some of the material I used for the TYF talk.

As you might have figured, the name Magna Cortica is a direct play on the Magna Carta, the so-called charter of liberties from nearly 800 years ago. The purpose of the Magna Carta was to clarify the rights that should be more broadly held, and the limits that should be placed on the rights of the king. All in all a good thing, and often cited as the founding document of a broader shift to democracy.

The Magna Cortica wouldn’t be a precise mirror of this, but it would follow a similar path: the Magna Cortica project would be an effort to make explicit the rights and restrictions that would apply to the rapidly-growing set of cognitive enhancement technologies. The parallel may not be precise, but it is important: while the crafters of the Magna Carta feared what might happen should the royalty remain unrestrained, those of us who would work on the Magna Cortica project do so with a growing concern about what could happen in a world of unrestrained pursuit of cognitive enhancement. The closer we look at this path of development, the more we see reasons to want to be cautious.

Of course, we have to first acknowledge that the idea of cognitive enhancement isn’t a new one. Most of us regularly engage in the chemical augmentation of our neurological systems, typically through caffeinated beverages. And while the value of coffee and tea includes wonderful social and flavor-based components, it’s the way that consumption kicks our thinking into high gear that usually gets the top billing. This, too, isn’t new: there are many scholars who correlate the emergence of so-called “coffeehouse society” with the onset of the enlightenment.

But if caffeine is our legacy cognitive technology, it has more recently been overshadowed by the development of a variety of brain boosting drugs. What’s important to recognize is that these drugs were not created in order to make the otherwise-healthy person smarter, they were created to provide specific medical benefits.

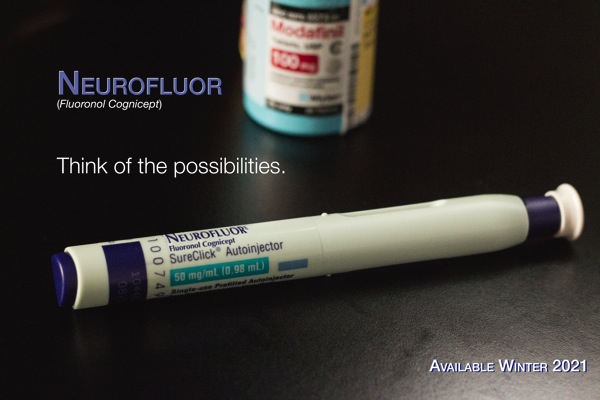

Provigil and its variants, for example, were invented as a means of treating narcolepsy. Like coffee and tea, it keeps you awake; unlike caffeine, however, it’s not technically a stimulant. Clear-headed wakefulness is itself a powerful boost. But for many users, Provigil also measurably improves a variety of cognitive processes, from pattern recognition to spatial thinking.

Much more commonly used (and, depending upon your perspective, abused) are the drugs devised to help people with attention-deficit disorder, from the now-ancient Adderall and Ritalin to more recent drugs like Vyvanse. These types of drugs are often a form of stimulant -- usually part of the amphetamine family, actually -- but have the useful result of giving users enhanced focus and greatly reduced distractibility.

These drugs are supposed to be prescribed solely for people who have particular medical conditions. The reality, however, is that the focus-enhancing, pattern-recognizing benefits don’t just go to people with disorders -- and these kinds of drugs have become commonplace on university campuses and in the research departments of high-tech companies around the world.

Over the next decade, we’re likely to see the continued emergence of a world of cognitive enhancement technologies, primarily but not exclusively pharmaceutical, increasingly intended for augmentation and not therapy. And as we travel this path, we’ll see even more radical steps, technologies that operate at the genetic level, digital artifacts mixing mind and machine, even the development of brain enhancements that could push us well beyond what’s thought to be the limits of “human normal.”

For many of us, this is both terrifying and exhilarating. Dystopian and utopian scenarios clash and combine. It’s a world of relentless competition to be the smartest person in the room, and unprecedented abilities to solve complex global problems. A world where the use of cognitive boosting drugs is considered as much of an economic and social demand as a present-day smartphone, and one where the diversity of brain enhancements allows us to see and engage with social and political subtleties that would once have been completely invisible. It's the world I explored a bit in my 2009 article in The Atlantic Monthly, "Get Smarter."

And such diversity is really already in play, from so-called “exocortical” augmentations like Google Glass to experimental brain implants to ongoing research to enhance or alter forms of social and emotional expression, including anger, empathy, even religious feelings.

There’s enormous potential for chaos.

There are numerous questions that we’ll need to resolve, dilemmas that we'll be unable to avoid confronting. Since this project may also be seen as a cautious “design spec,” what would we want in an enhanced mind? What should an enhanced mind be able to do? Are there aspects of the mind or brain that we should only alter in case of significant mental illness or brain injury? Are there aspects of a mind or brain we should never alter, no matter what? (E.g., should we ever alter a person’s sense of individual self?)

What are the the rights and responsibilities we would have to the non-human minds that would be enhanced and potentially created along the way to human cognitive enhancement. Animal testing would be unavoidable. What would we owe to rats, dogs, and apes (etc.) with potentially vastly increased intellect? Similarly, whole-brain neural network simulations, like the Blue Brain project, offer a very real possibility of the eventual creation of a system that behaves like -- possibly even believes itself to be -- a human mind. What responsibilities would we have towards such a system? Would it be ethical to reboot it, to turn it off, to erase the software?

The legal and political aspects cannot be ignored. We would need extensive discussion of how this research will be integrated into legal frameworks, especially with the creation of minds that don’t fall neatly into human categories. And as it’s highly likely that military and intelligence agencies will have a great deal of interest in this set of projects, the role that such groups should have will need to be addressed -- particularly once a “hostile actor” begins to undertake similar research.

Across all of this, we'd have to consider the practices and developments that are not currently considered near-term feasible, such as molecular nanotechnologies, as well as techniques not yet invented or conceived. How can we make rules that apply equally well to the known and the unknown?

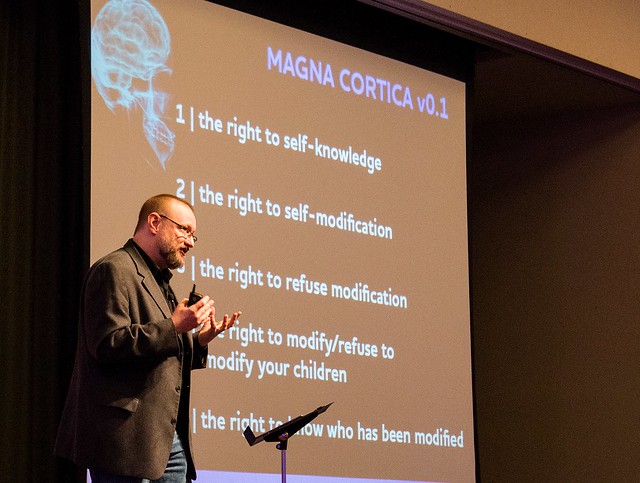

All of these would be part of a Magna Cortica project. But for today, I’d like to start with five candidates for inclusion as basic Magna Cortica rights, as a way of… let’s say nailing some ideas to a door.

- The right to self-knowledge. Likely the least controversial, and arguably the most fundamental, this right would be the logical extension of the quantified self movement that's been growing for the last few years. As the ability to measure, analyze, even read the ongoing processes in our brains continues to expand, the argument here is that the right to know what’s going on inside our own heads should not be abridged.

Of course, there’s the inescapably related question: who else would have the right to that knowledge?

- As the Maker movement says, if you can’t alter something, you don’t really own it. In that spirit, it’s possible that a Magna Cortica could enshrine the right to self-modification. This wouldn’t just apply to cognition augmentation, of course; the same argument would apply to less practical, more entertainment-oriented alterations. And as we’ve seen around the world over the last year, the movement to make such things more legal is well underway.

- The flip side of the last right, and potentially of even greater sociopolitical importance, is a right to refuse modification. To just say no, as it were. But while this may seem a logical assertion to us now, as these technologies become more powerful, prevalent, and important, refusing cognitive augmentation may come to be considered as controversial and even irresponsible as the refusal to vaccinate is today. Especially in light of…

- A right to modify or to refuse to modify your children. It has to be emphasized that we already grapple with this question every time a doctor prescribes ADHD drugs, when both saying yes and saying no can lead to accusations of abuse. And if the idea of enhancements for children rather than therapy seems beyond the pale, I’d invite you to remember Louise Brown, the first so-called “test tube baby.” The fury and fear accompanying her birth in 1978 is astounding in retrospect; even the co-discoverer of the structure of DNA, James Watson, thought her arrival meant "all Hell will break loose, politically and morally, all over the world." But today, many of you reading this either know someone who has used in-vitro fertilization, have used it yourself, or may even be a product of it.

- Finally, there’s the potential right to know who has been modified. This suggested right seems to elicit an immediate reaction of visions of torches and pitchforks, but we can easily flip that script around. Would you want to know if your taxi driver was on brain boosters? Your pilot? Your child’s teacher? Your surgeon? At the root of all of this is the unanswered question of whether the identification as having an augmented mind would be seen as something to be feared… or something to be celebrated.

And here again we encounter the terrifying and the exhilarating: we are almost certain be facing these questions, these crises and dilemmas, over the next ten to twenty years. As long as intelligence is considered a competitive advantage in the workplace, in the labs, or in high office, there will be efforts to make these technologies happen. The value of the Magna Cortica project would be to bring these questions out into the open, to explore where we draw the line that says “no further,” to offer a core set of design principles, and ultimately to determine which pathways to follow before we reach the crossroads.

A diverse assortment of legal, bioscience, psychology, and ethics academics

A diverse assortment of legal, bioscience, psychology, and ethics academics  Discussions of the implications of the augmentation of our biological bodies with prosthetic technologies can be found quite readily in the esoteric discourses of self-described

Discussions of the implications of the augmentation of our biological bodies with prosthetic technologies can be found quite readily in the esoteric discourses of self-described  I had a similar reaction when I learned that the "

I had a similar reaction when I learned that the " It strikes me that there's a likely split in the near-term evolution of human-environment robots in the years to come. Some robots, those meant to interact on a regular basis with humans, will likely take on stronger biomorphic appearances and behaviors, usually in order to deter abusive behavior. A small number of robots, intended to provide

It strikes me that there's a likely split in the near-term evolution of human-environment robots in the years to come. Some robots, those meant to interact on a regular basis with humans, will likely take on stronger biomorphic appearances and behaviors, usually in order to deter abusive behavior. A small number of robots, intended to provide

Let me tell you, being a cyborg isn't all it's cracked up to be. But it might be, sooner than you expect.

Let me tell you, being a cyborg isn't all it's cracked up to be. But it might be, sooner than you expect. These aren't just dumb amplifiers; they're little digital signal processors, small enough to fit into the ear canal, and smart enough to know when to boost the input and when to leave it alone. They're programmable, too (sadly, not by the end-user -- programming requires an acoustic enclosure, not just a computer connection). And here's where therapeutic augmentation starts to fuzz into enhancement: one of the program modes I'm considering would give me far better than normal hearing, allowing me to pick up distant conversations like I was standing right there.

These aren't just dumb amplifiers; they're little digital signal processors, small enough to fit into the ear canal, and smart enough to know when to boost the input and when to leave it alone. They're programmable, too (sadly, not by the end-user -- programming requires an acoustic enclosure, not just a computer connection). And here's where therapeutic augmentation starts to fuzz into enhancement: one of the program modes I'm considering would give me far better than normal hearing, allowing me to pick up distant conversations like I was standing right there.

How'd you like a computer in your head?

How'd you like a computer in your head?