Participatory Panopticon: 2019

In April of 2004--just a bit over 15 years ago--I posted this question to Worldchanging:

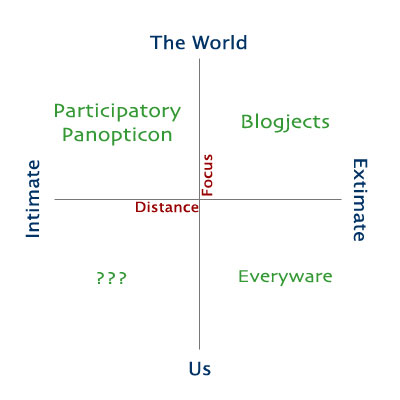

"What happens when you combine mobile communications, always-on cameras, and commonplace wireless networks?" I called the answer the Participatory Panopticon.

Remember: at that point in time, Blackberry messaging was the height of mobile communication, cameras in phones were rare and of extremely poor quality, and EDGE was the most common form of wireless data network. Few people had truly considered what the world might look like as all of these systems continued to advance.

The core of the Participatory Panopticon concept was that functionally ubiquitous personal cameras with constant network connections would transform much of how we live, from law enforcement to politics to interpersonal relationships. We'd be able to--even expected to--document everything around us. No longer could we assume that a quiet comment or private conversation would forever remain quiet or private.

The Participatory Panopticon didn't simply describe a jump in technology, it envisioned the myriad ways in which our culture and relationships would change in the advent of a world of unrelenting peer-to-peer observation.

Here's the canonical version of the original argument: the text of the talk I gave at Meshforum in 2005. It's long, but it really captures what I was thinking about at the time. As with any kind of old forecast, it's interesting to look for the elements that were spot-on, the ones that were way off, and the ones that weren't quite right but hinted at a change that may still be coming. I like to think about this as engaging in "forecast forensics," and there's a lot to dig through in this talk.

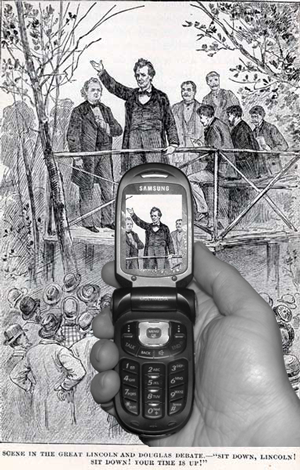

A surprising amount of what I imagined 15 years ago about the Participatory Panopticon has borne out: The interweaving of social networks and real time commentary, the explosion of "unflattering pictures and insulting observations," the potential for citizens to monitor the behavior (and misbehavior) of public servants, even (bizarrely) the aggressiveness of agents of copyright going after personal videos that happen to include music or TV in the background. The core of the Participatory Panopticon idea is ubiquity, and that aspect of the forecast has succeeded beyond my wildest expectations.

If you were around and aware of the world in 2005, you may remember what digital cameras were like back then. We were just at the beginning of the age of digital cameras able to come close to the functionality and image quality of film cameras, if you could afford a $2,000 digital SLR. Even then, the vast majority of digital cameras in the hands of regular people were, in a word, crap. The cameras that could be found on mobile phones were even worse--marginally better than nothing. Marginally. The idea of a world of people constantly taking pictures and video on their personal devices (not just phones, but laptops, home appliances, and cars) seemed a real leap from the world we lived in at the time. A world where all of these pictures and videos would then matter to our politics, our laws, and our lives, seemed an even greater leap.

But the techno-cultural jolt I termed the Participatory Panopticon has profoundly changed our societies to a degree that it's sometimes hard to remember what life was like beforehand. Today's "Gen Z" youth have never been conscious of a world without the Participatory Panopticon. They're a generation that has been constantly surrounded by cameras held by family, friends, and most importantly, themselves.

We may not always recognize just how disorienting this has been, how much it has changed our sense of normal. One bit from the essay that still resonates today concerns the repercussions of never letting go of the documented past:

Relationships--business, casual or personal--are very often built on the consensual mis-rememberings of slights. Memories fade. Emotional wounds heal. The insult that seemed so important one day is soon gone. But personal memory assistants will allow people to play back what you really said, time and again, allow people to obsess over a momentary sneer or distracted gaze. Reputation networks will allow people to share those recordings, showing their friends (and their friends' friends, and so on) just how much of a cad you really are.

(Okay, forget the "personal memory assistants" and "reputation networks" jargon, and substitute "YouTube" and "Instagram" or something.)

Think about what happens today when someone's offensive photo or intentionally insulting joke from a decade or two ago bubbles back up into public attention. Whether or not the past infraction was sufficiently awful as to be worthy of present-day punishment is beside the point: one of the most important side-effects of the Participatory Panopticon (and its many connected and related technologies and behaviors) is that we've lost the ability to forget. This may be a good thing; it may be a tragedy; it is most assuredly consequential.

But if that aspect of the Participatory Panopticon idea was prescient, other parts of the forecast were excruciatingly off-target.

Although there were abundant inaccuracies with the technological scenarios, the one element that stands out for me as being the most profoundly wrong is the evident--and painfully naiive--trust that transparency is itself enough to force behavioral changes. That having documentation of misbehavior would, in and of itself, be sufficient to shame and bring down bad actors, whether they were forgetful spouses, aggressive cops, or corrupt politicians. As we've found far too many times as the real-world version of the Participatory Panopticon has unfolded, transparency means nothing if the potential perpetrators can turn off the cameras, push back on the investigators, or even straight up deny reality.

Transparency without accountability is little more than voyeurism.

There are elements of the Participatory Panopticon concept that haven't emerged, but also can't be dismissed as impossible. Two in particular stand out as having the greatest potential for eventual real-world consequences.

The first is the more remote of the two, but probably more insidious. We're on the cusp of the common adoption of wearable systems that can record what's around us, systems that are increasingly indistinguishable from older, "dumb" versions of the technology. Many of the privacy issues already extant around mutual snooping will be magnified, and new rounds of intellectual property crises will emerge, when the observation device can't be distinctly identified. If my glasses have a camera, and I need the glasses to see, will I be allowed to watch a movie? If I can tap my watch and have it record a private conversation or talk without anyone around me noticing, will we even be allowed to wear our wearables anywhere?

(By the way, I can already do that with my watch. Be warned.)

The second might be the most important element of the Participatory Panopticon story, even if it received little elaboration in the 2005 talk. It's included there almost as a throwaway idea, in a brief aside about the facility with which pictures can be altered:

It's easy to alter images from a single camera. Somewhat less simple, but still quite possible, is the alteration of images from a few cameras, owned by different photographers or media outlets.But when you have images from dozens or hundreds or thousands of digital cameras and cameraphones, in the hands of citizen witnesses? At that point, I start siding with the pictures being real.

The power of the Participatory Panopticon comes not just from a single person being able to take a picture or record a video, but from the reinforcement of objective reality that can come from dozens, hundreds, thousands of people independently documenting something. A mass of observers, each with their own perspectives, angles, and biases, can firmly establish the reality of an event or an action or a moment in a way that no one official story could ever do.

It's common to ask what we can do about the rise of "deep fakes" and other forms of indistinguishable-from-reality digital deceptions. Here's one answer. The visual and audio testimony of masses of independent observers may be an effective counter to a convincing lie.

In a recent talk, I argued that "selfies" and other forms of digital reflection aren't frivolous acts of narcissism, but are in fact a form of self-defense--an articulation that I am here, I am doing this, I can claim this moment of my life.

In 2009, the Onion offered a satiric twist on this concept, in yet another example of dystopian humor predicting the future.

As this suggests, my images aren't just documentation of myself, they're documentation of everyone around me. My verification of my reality also verifies the reality of those around me, and vice versa... whether we like it or not. Like so many of the consequences of the Participatory Panopticon, its manifestation in the real world can occasionally be brutal. With "Instagram Reality" mockery, for example, the editing and "improvement" of images of social network influencers is called out by other people's pictures showing their real appearance.

It's harsh and more than a little misogynist. But that's the ugly reality of the Participatory Panopticon: it was never going to change who we are. It was really only going to make it harder to hide it.

Foresight (forecasts, scenarios, futurism, etc.) is the most useful when it alerts us to emerging possible developments that we had not otherwise imagined. Not just as a "distant early warning," but as a vaccination. A way to become sensitive to changes that we may have missed. A way to start to be prepared for a disruption that is not guaranteed to happen, but would be enormously impactful if it did. I've had the good fortune of talking with people who heard my Participatory Panopticon forecast and could see its application to their own work in human rights, in environmentalism, and in politics. The concept opened their eyes to new ways of operating, new channels of communication, and new threats to manage, and allowed them to act. The vaccination succeeded.

It's good to know that, sometimes, the work I do can matter.

This does not seem like a good combination:

This does not seem like a good combination:

(Well, "new" in the sense of it's the most recent; it actually went up earlier this week, I just didn't get around to linking to it here. Ahem.)

(Well, "new" in the sense of it's the most recent; it actually went up earlier this week, I just didn't get around to linking to it here. Ahem.)

Microsoft/Danger/T-Mobile to millions of Sidekick users:

Microsoft/Danger/T-Mobile to millions of Sidekick users:

Participatory Panopticon edition!

Participatory Panopticon edition!

What happens when not only have the tools of documenting the world become democratized, so too have the tools for manipulating our interpretations of reality?

What happens when not only have the tools of documenting the world become democratized, so too have the tools for manipulating our interpretations of reality?

Whenever I talk about the participatory panopticon, one issue grabs an audience more often than anything else -- privacy. But the more I dig into the subject, the more it becomes clear that the real target of the panopticon technologies isn't privacy, but deception. We're starting to see the onset of a variety of technologies allowing the user to determine with some degree of accuracy whether or not the subject is lying. The most promising of these technologies use

Whenever I talk about the participatory panopticon, one issue grabs an audience more often than anything else -- privacy. But the more I dig into the subject, the more it becomes clear that the real target of the panopticon technologies isn't privacy, but deception. We're starting to see the onset of a variety of technologies allowing the user to determine with some degree of accuracy whether or not the subject is lying. The most promising of these technologies use

Web-enabled personal medical information technologies have been a standard item in the futurist's scrapbook for a few years now. It's one of those concepts that's hard to imagine not happening: the demographic, technological, and market pressures for Internet-mediated health technologies aimed at the elderly have terrific momentum.

Web-enabled personal medical information technologies have been a standard item in the futurist's scrapbook for a few years now. It's one of those concepts that's hard to imagine not happening: the demographic, technological, and market pressures for Internet-mediated health technologies aimed at the elderly have terrific momentum.

Okay, this is kinda cool.

Okay, this is kinda cool. Justin of

Justin of  This month's

This month's  The

The  Just a couple of quick items on the participatory panopticon front:

Just a couple of quick items on the participatory panopticon front: It looks like the first draft version of the

It looks like the first draft version of the  The first day of the

The first day of the  I love to watch the future take shape.

I love to watch the future take shape.