Even among many of the generally tech-friendly and realistic bright green types, the automobile remains an irritant. It's not simply that the petroleum-powered internal combustion engine is an ecological disaster; the automobile, historically, has been a catalyst for many of the more damaging developments in our social geography, from the spread of suburbia and exurbia to the elimination (in many locations) of light rail lines, and continues to enable the proliferation of economic and social institutions of dubious long-term benefit (such as big-box retailers). In many ways, the automobile is the canonical example of a trigger for long-term, unanticipated and undesired results. If we think of the car in this way, it's clear that even shifting entirely to electric cars, biofuel cars, or cars that ran on pixie dust, would still enable many of the larger social pathologies that damage our climate, ecological, and social systems.

Even among many of the generally tech-friendly and realistic bright green types, the automobile remains an irritant. It's not simply that the petroleum-powered internal combustion engine is an ecological disaster; the automobile, historically, has been a catalyst for many of the more damaging developments in our social geography, from the spread of suburbia and exurbia to the elimination (in many locations) of light rail lines, and continues to enable the proliferation of economic and social institutions of dubious long-term benefit (such as big-box retailers). In many ways, the automobile is the canonical example of a trigger for long-term, unanticipated and undesired results. If we think of the car in this way, it's clear that even shifting entirely to electric cars, biofuel cars, or cars that ran on pixie dust, would still enable many of the larger social pathologies that damage our climate, ecological, and social systems.

At the same time, the typical solutions offered in response -- remaking urban design, increased bus and rail use, increased walking and biking -- have significant drawbacks. The first is expensive and slow, and the latter two impose significant limitations to what one can accomplish over the course of the day. I sometimes think that calls for everyone to give up cars are sufficiently unrealistic that they may actually be counter-productive: if the only alternative under discussion is to completely rebuild our cities and make everybody walk to the bus stop, cars will remain firmly in place as the dominant transportation model.

It doesn't have to be that way. I have from the outset considered it a strength of the bright green philosophy that it values workable idealism, and recognizes the futility of telling people that the only way to solve problems is to make their lives viscerally worse. Moreover, one of the cornerstone concepts of bright green environmentalism is a recognition of the strength of distributed solutions over centralized technologies. Telling people just to give up cars is a startlingly old green concept for the new green generation.

To be clear, I'm not dismissing urban redesign and greater access to public transit & walking out of hand; the former is a terrific medium-term goal, and the latter is certain to be part of the solution to the looming climate disaster, especially as better urban designs make non-car transit more efficient. But demands for the immediate adoption of these approaches seem blind to the underlying reasons why the automobile culture is so deeply entrenched in Western society, and why it has become so attractive to nations seeing rapid economic development.

[This is a personal issue for me. Right now, I live some distance from my once/twice-weekly workplace, the Institute for the Future; because of the current housing market, selling our place and moving in closer isn't an option. If I take public transit, I must ride BART to a Cal-Train station, and take that to Palo Alto (fortunately, IFTF is just a block from the station there). If I time it just right, it will take no less than two hours -- longer, of course, if there's a delay and I miss my transfer (which happened the very first time I took the route). If I drive (my hybrid, naturally), it typically takes me 90 minutes, and can take as little as 75 minutes if the traffic is completely clear. Still a very long commute (fortunately, it's not daily), but with greater flexibility as to when I can leave and which route I can take if there's an unexpected delay. For now, I tend to swap back and forth between the two modes of transit.]

One way of re-examining this subject is to stop thinking about cars as "cars," and to start thinking about them in terms of the services they offer. This sort of abstraction is commonplace in the business consulting field -- it's not a carpet, it's a floor covering service. Surprisingly, that simple shift in perspective can sometimes elicit novel ideas. But it's important that new services that replace the old can replicate or improve upon the capabilities of the previous model.

Thinking about cars in this way, I would argue that a car is a way of providing:

- Personal mobility. The most obvious characteristic of the automobile, personal mobility means more than simply getting from one place to another. It encompasses: range and speed (being able to travel for great distances in a reasonable amount of time); carrying capacity (being able to carry items too large, bulky or awkward to carry by hand any significant distance); destination flexibility (being able to travel to one's exact destination, and to change destination along the way); and operational flexibility (being able to use the car for both short and long-range travel, to carry very little or a large amount, and to change uses mid-stream).

- Personal expression. Perhaps less obviously important, personal expression is in reality a key element of how drivers choose their vehicles. While this may seem like a superficial issue, consider: in a world where home ownership is out of reach for many people, the automobile becomes the biggest investment one will personally make -- the desire to have the car reflect one's personality (through color, design, or brand) is a near-inevitable result. As we move to urban models of higher-density shared buildings, such desire for personal expression via automobiles may actually increase.

- Independence. This is related to the previous two, and can best be summed up as: being able to use the car in a way that is not contingent upon the desires and needs of others. Total independence is not possible, of course (at the very least, one is supposed to obey traffic laws), but superficial independence -- being able to choose the radio station, to travel at any time of day or night, to be as messy or as neat as one wishes -- clearly is.

Thought of in this way, it's easy to see why urban redesign, public transit and walking/biking are having such a hard time replacing automobile use for most people. There are exceptions; for some people, these substitutions may be entirely adequate. But even people getting around fine without a car in San Francisco, New York, or London will acknowledge how overwhelmingly abundant cars are in those cities, and they aren't just the cars brought in by people from the 'burbs.

There are more innovative alternatives, and these offer some promise. Car-sharing allows many of the benefits of car use without the trappings of ownership. Limited-range micro-cars (think the Reva or Zap) remain personal transportation, but are much smaller and have a much smaller footprint (as they're often all-electric). Both fall short of being a total replacement for today's autos, however, for a somewhat subtle reason. Most of the time, such alternatives would actually be fine. They're perfect for the regular, predictable travel that we tend to undertake, and the running around town that makes up the majority of our vehicle trips. But for the outlying uses, such as the unexpected need to drive somewhere at 3am, take a longer-than-usual trip, or carry something especially large -- the alternatives fail. And since the outlying uses, while uncommon, are still relatively frequent, many people hesitate to give up the ability to accomplish them readily.

So, what would work to replace car culture as it is currently manifest but still perform the services that the modern automobile offers?

Here's one scenario that comes to mind:

Cars as LEGO.

I back out of the parking shed, slowly -- I know that the p2p nav system wouldn't let me continue if there was another car coming, but I have old habits. The car, a 2017 Honda Civic M, is still a bit weird to drive. It feels like it's missing half the car: no real front-end to speak of, and a trunk that barely qualifies for the name. It's roomy on the inside, though, and I know that the safety measures are top notch (they meet race car specs).

Normally, I'd just drive from home to the train. Plugging into the train is one of the times that the law requires that drivers give up control to the nav system; it's not that people can't maneuver the cars into the slots, but that careful human drivers are just a lot slower than navs. Getting several dozen cars into and out of train slots in a one-minute stop is a real trick. Apparently BART hired theme park designers who know just how to get people on and off roller coasters most efficiently, but the basics are the same with most platooning systems, whether on trains or freeways.

BART's going to have to add some more platoon units to their trains; lately, I've had to wait for two or three trains to pass through before getting a slot. It's worth the wait. No parking worries at the station, and I can drive to work easily once I get to Palo Alto. At the end of the day, I can pick up a return train or just head home directly. Unmodded, though, the Civic M just barely gets freeway speeds, so I tend to stick with the train.

Today, I'm going for a mod. I need to make a quick run out of the area to visit my mom, and the train station near where she is doesn't yet have rail platoon roll on/roll off setup. Getting to San Luis with the car as it is would take way too long, so I'm going to pick up a "go pack" -- an engine & battery booster kit. That'll get me up to freeway speeds and give me the range I need.

I pull around the corner to where the Shell station used to be. Gas stations are hard to find these days, but they're still around -- by law, there's one every 200 miles along major highways to support legacy drivers and vehicles still requiring petroleum, and bigger towns usually have one or two. Most gas stations have been converted into modding stops: drive in, select the desired modification packs, let the system plug them in, pay and go. Takes about as much time as gassing up an empty tank used to, and competition between vehicle modification service providers (VSPs) keeps the prices reasonable. In this case, the mod stop is out of basic go packs, and I don't see a need to step up to the "sport utility" pack. Fortunately, there's another VSP just down the street.

Although every car maker still has its own set of nameplates and designs, the mod pack system is blissfully standardized. The go pack I get plugged into my Civic M would work just as well on a Micro-Prius or a Volvochev Daytripper convertible. Most car makers' warranties include a lifetime retrofit guarantee, which I suppose is strong motivation for adhering to the mod pack standard. The range of mod options is pretty good, regardless; I could, if I wanted, even get a truck mod installed, but that requires some post-mod safety checks, and I've only needed the added carrying capacity once or twice.

The nice thing about the mod system is that, when I'm done, I just drop the mod off at a convenient VSP. The mods are geotagged so the owner (who may or may not be the original VSP) knows where they are and which vehicles are using them. A sorting algorithm at the VSP asks the car's nav for destination info in order to offer up an appropriate unit needing to head back home. It's not unusual for high school students to make a bit of money on the side taking a truck mod out to collect wayward go packs that haven't made it back home in awhile.

Some people who need daily access to a longer range or heavier cargo capacity buy permanent mods, but most of us just either do one-time rentals or discounted service plans. In a way, it's kind of like treating a car like a mobile phone.

What's really cool is the hacker community that has sprung up around this system. I've seen all kinds of home-brew car mods in MAKE: amphibious packs, emergency relief systems (turning the car into a mobile power supply and communication station), even a "swarm charge" kit that'll let you share power from your car with another vehicle in a platoon. Now I just need one that'll wash the car for me.

There are plenty of nits to pick in this scenario. It's tech-heavy, and would require some infrastructure replacement, although not necessarily to the same scale as the urban redesign model (but neither would it prevent or slow a redesign). Getting car makers to agree on a standard mod design would be a nightmare, and would be almost as hard as convincing drivers that it's okay to go without the massive trunk or room for 14. It would work best with electric-only vehicles, but (with some changes) would likely be okay for plug-in hybrid, H2 fuel cell, or possibly even biofuel vehicles.

The biggest objection is likely that it would do nothing to alter the existing suburban/exurban-automobile model. That's true, but at the same time I would say that it's an enabler for that kind of change, opening urban life up to people who otherwise wouldn't consider it. Smaller vehicles are easier to fit into denser environments, and roll-on/roll-off train systems would make rail commuting much more accessible to people with destinations beyond a reasonable distance from a station. Personal mobility, personal expression, and independence remain satisfied, but so too are the needs of a denser, more energy/carbon-conscious urban environment.

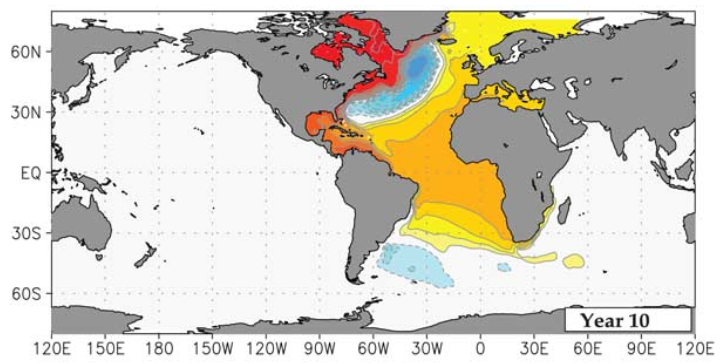

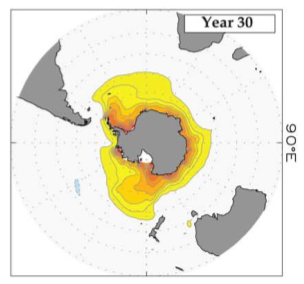

If you follow the online climate discussion, you've undoubtedly run across the mention of something called the "

If you follow the online climate discussion, you've undoubtedly run across the mention of something called the "

A

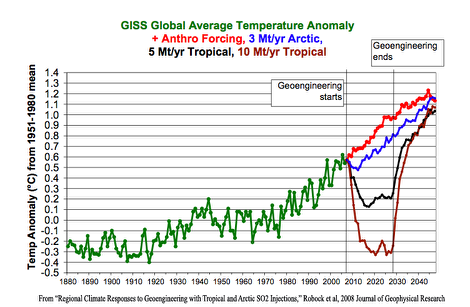

A  An aerosol known as "

An aerosol known as "

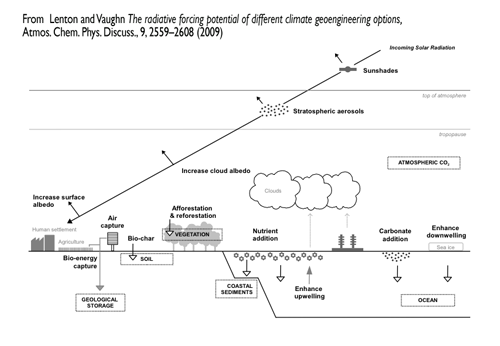

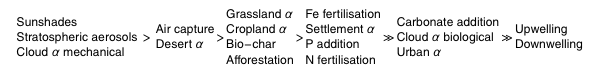

I've been writing about geoengineering since 2005, and have even published a short book on the subject (

I've been writing about geoengineering since 2005, and have even published a short book on the subject (

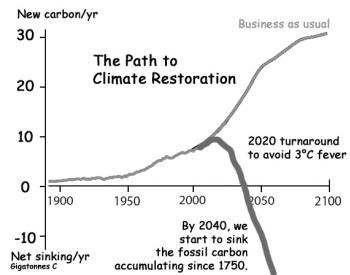

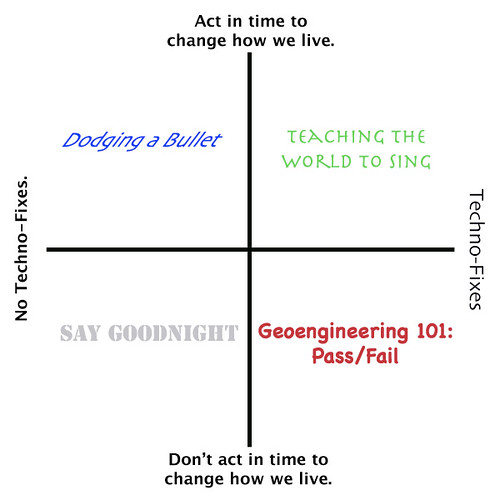

It's fascinating to watch the evolution of the mainstream media coverage of the geoengineering concept. I'm actually pretty pleasantly surprised: most of the articles I've seen have had an overall tone of caution about the proposals, even while recognizing that if we end up using geoengineering technologies, it's because things have gotten so bad that we're down to our last-ditch methods of avoiding disaster. The basics of the stories have been pretty consistent: we're in an even bigger climate mess than we thought, so real scientists have begun to consider options for climate modification that they might have dismissed in the past, simply to head off catastrophe; nonetheless, more research needs to be done. I haven't seen any news stories (as opposed to opinion pieces, or blog articles) that even imply that geoengineering would be considered a replacement for decarbonization, and I'm seeing fewer news articles that start from the perspective that such climate modification is inherently wrong, period.

It's fascinating to watch the evolution of the mainstream media coverage of the geoengineering concept. I'm actually pretty pleasantly surprised: most of the articles I've seen have had an overall tone of caution about the proposals, even while recognizing that if we end up using geoengineering technologies, it's because things have gotten so bad that we're down to our last-ditch methods of avoiding disaster. The basics of the stories have been pretty consistent: we're in an even bigger climate mess than we thought, so real scientists have begun to consider options for climate modification that they might have dismissed in the past, simply to head off catastrophe; nonetheless, more research needs to be done. I haven't seen any news stories (as opposed to opinion pieces, or blog articles) that even imply that geoengineering would be considered a replacement for decarbonization, and I'm seeing fewer news articles that start from the perspective that such climate modification is inherently wrong, period.

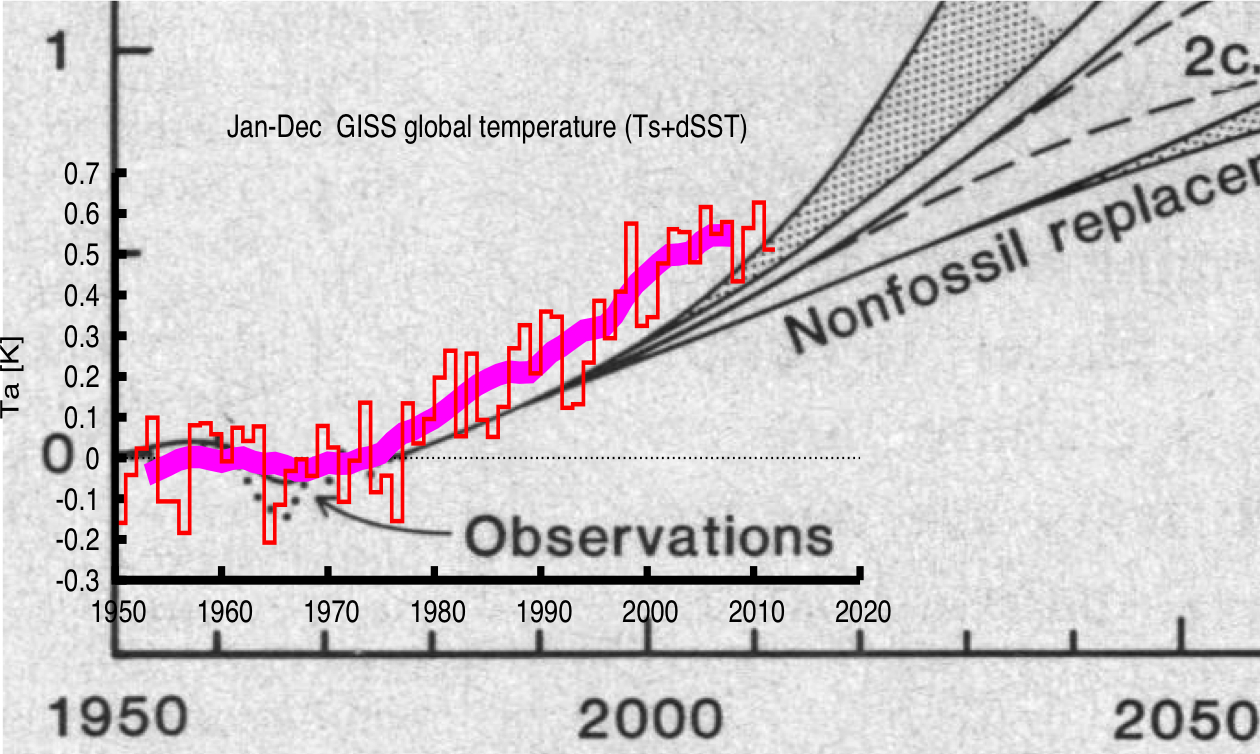

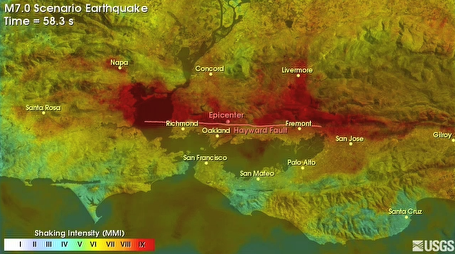

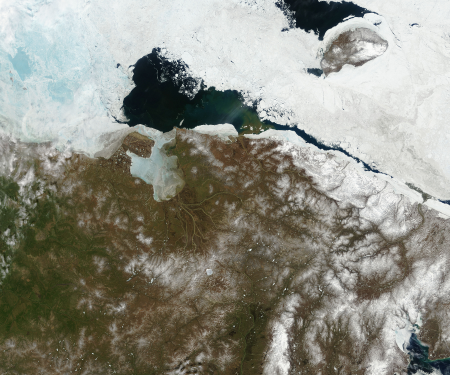

Okay, it's a standard presumption that global warming is going to make major heat waves more likely, in more places, lasting longer. Moreover, because of thermal inertia and climate commitment (not to mention how stubborn traditional politics seems to be on environmental issues), we're going to continue to see warming temperatures for at least a couple more decades. In short, the kind of heat I've been seeing locally over the last week -- multi-day 110°+ temperatures -- may be an increasingly common event for some time to come.

Okay, it's a standard presumption that global warming is going to make major heat waves more likely, in more places, lasting longer. Moreover, because of thermal inertia and climate commitment (not to mention how stubborn traditional politics seems to be on environmental issues), we're going to continue to see warming temperatures for at least a couple more decades. In short, the kind of heat I've been seeing locally over the last week -- multi-day 110°+ temperatures -- may be an increasingly common event for some time to come.

The grand myth of environmentalism is that it's all about saving the Earth.

The grand myth of environmentalism is that it's all about saving the Earth.

Foreign Policy has just published a substantially updated version of my article "

Foreign Policy has just published a substantially updated version of my article "

Even among many of the generally tech-friendly and realistic bright green types, the automobile remains an irritant. It's not simply that the petroleum-powered internal combustion engine is an ecological disaster; the automobile, historically, has been a catalyst for many of the more damaging developments in our social geography, from the spread of suburbia and

Even among many of the generally tech-friendly and realistic bright green types, the automobile remains an irritant. It's not simply that the petroleum-powered internal combustion engine is an ecological disaster; the automobile, historically, has been a catalyst for many of the more damaging developments in our social geography, from the spread of suburbia and  I'm packing to head off for a few days (it's ostensibly a vacation, so I'll only be working part of the time), but I thought that this was something that should be at the top of your web reading list.

I'm packing to head off for a few days (it's ostensibly a vacation, so I'll only be working part of the time), but I thought that this was something that should be at the top of your web reading list. This week's Newsweek contains an article ("

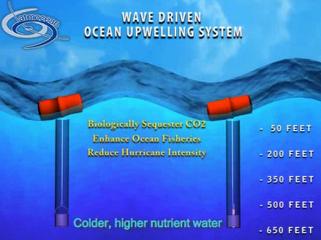

This week's Newsweek contains an article (" The latest Popular Science focuses on a

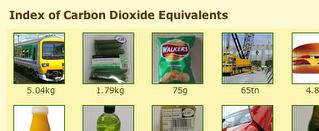

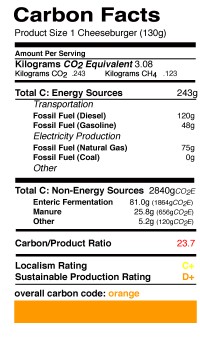

The latest Popular Science focuses on a  So the folks who asked about milk's footprint run what might come to be a useful listing of the carbon footprints of a variety of everyday items. It's in the UK, so some of the examples aren't entirely universal (a train from London to York, for example), but it's a good start. As of today, they have 21 items (including... well, you know).

So the folks who asked about milk's footprint run what might come to be a useful listing of the carbon footprints of a variety of everyday items. It's in the UK, so some of the examples aren't entirely universal (a train from London to York, for example), but it's a good start. As of today, they have 21 items (including... well, you know).

Today's Christian Science Monitor has a thoughtful

Today's Christian Science Monitor has a thoughtful  Bruce Sterling's

Bruce Sterling's  The "

The "

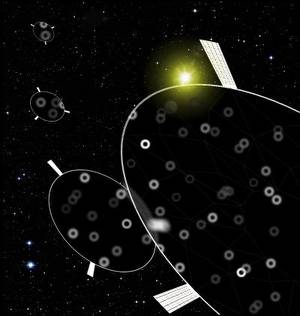

This has "duh... why did we think of this before!" written all over it: a "redundant array of inexpensive disks" to cool the Earth.

This has "duh... why did we think of this before!" written all over it: a "redundant array of inexpensive disks" to cool the Earth. St. Olaf College, a small private university in Minnesota, recently decided to add a

St. Olaf College, a small private university in Minnesota, recently decided to add a