BREAKING: President's Advisors Mull Resignation, Sources Claim

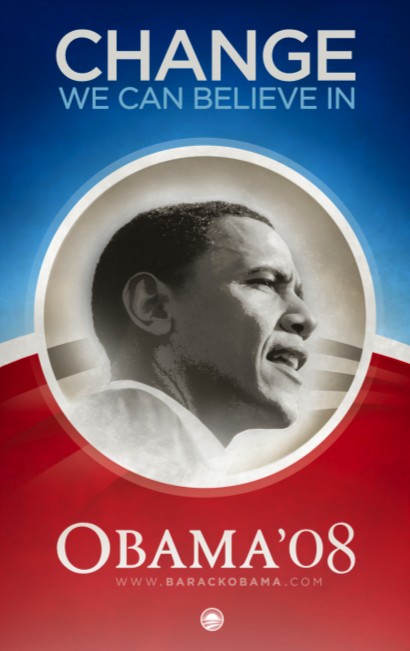

This news report slipped through a wormhole from an alternate universe where a sufficient number of voters in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania gave those states to Hillary Clinton in 2016, thereby making her President of the United States. Otherwise, the election happened just as in our universe. --Jamais Cascio

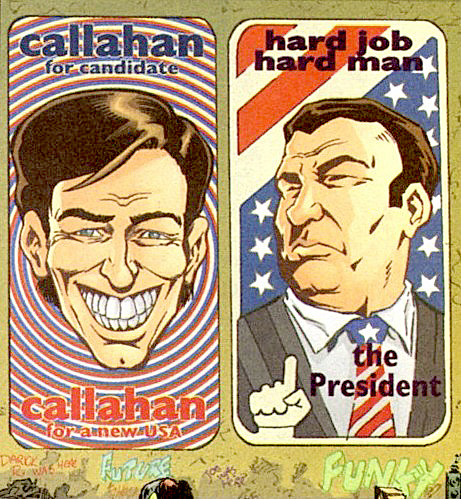

Key advisors have reportedly asked President Hillary R. Clinton to consider resignation before the 2018 mid-term elections, in a bid to avoid the troubling likelihood of the President being removed from office in 2019.

"It's absolutely ludicrous and infuriating," said a senior advisor who requested anonymity to discuss internal debates. "We know that HRC hasn't broken any laws, but the repeated impeachment hearings, on top of the constant Congressional foot-dragging on confirmations and votes, have made governing impossible.

"Resignation would be humiliating, but not as much as being the first President ever removed from office."

The Democrats face a challenging map for the 2018 mid-term elections. More Democrat-held seats in the Senate are up for election in 2018 than those held by Republicans, and several of those seats are in states that went for the Republican candidate in the 2016 Presidential election. In addition, the President's party historically faces the loss of Congressional seats in the mid-terms.

Enthusiasm among Democratic voters is markedly lower than during the 2016 campaign, with the most prominent voices being those in support of Clinton's rival in the 2016 primary, Senator Bernie Sanders. Senior Democrats fear that Sanders supporters will try to defeat more moderate incumbent Democrats in the 2018 primaries, potentially losing otherwise reliable Senate seats in November.

Although the likelihood remains low, the White House nonetheless faces a very real possibility that the Republicans will take enough seats in the Senate to reach the 67 votes, or two-thirds of the Senate, required for conviction in an impeachment process.

President Clinton faced her first impeachment vote in the House of Representatives in June of 2017. The charges were a mish-mash of accusations leveled by the 2016 Republican Presidential candidate Donald J. Trump along with various crimes Clinton was alleged to have committed during the period between her husband's term in office and her selection as Secretary of State by President Obama.

Legal scholars universally panned the legitimacy of the impeachment, but stressed that impeachment is a political process, and not subject to the same rules of evidence required in court. The Senate vote against conviction was a lopsided 88 to 11, with all Democrats and most Republicans voting to acquit.

Clinton's second impeachment trial came early in 2018, after accusations that her use of force in Syria, in response to Assad's widespread use of chemical weapons, violated the Constitution. As had both Presidents Bush and Obama, President Clinton relied on existing authorizations of military force to legally justify strikes on new targets. Although many Constitutional scholars had argued that the previous Presidents' reliance on existing authorization was inappropriate and possibly illegal, Congress only came to accept that argument after Clinton's election. This time, the Senate vote was much closer, with 53 Senators voting to convict (all Republicans with two Democrats), and 47 Senators voting to acquit.

"The impeachment hearings were a circus, and they distracted attention from the real problem -- the refusal of Congress to act on Clinton's appointments and to pass a real budget," argued Tom Vilsack, President Clinton's chief of staff.

The Supreme Court's preparations to enter its next term again with only eight seated Justices highlights the confirmation problem. Just a handful of President Clinton's appointees have received Senate confirmation. Senate Majority Leader McConnell was especially slow to bring Supreme Court nominee Merrick Garland to a vote, leading to civil lawsuits against the Republican leader. Garland, originally nominated by President Obama then re-nominated by Clinton, was ultimately rejected by the Senate along party lines.

Similarly, the normal legislative process has all but disappeared. Few bills supported by the White House have passed Congress, and nearly all of the bills championed by Congressional Republicans have received a veto from the President. Executive orders and narrowly-tailored compromise packages have allowed the United States to avoid defaulting on debt and to provide assistance to Houston and Puerto Rico in the aftermath of the 2017 hurricane season, but little else. A fragile budget truce freezing the 2016 budget in place allowed the warring branches to avoid a full government shutdown, but analysts on all sides assert that this situation cannot last much longer.

The least productive Congress in history, a perpetually-looming government shutdown, and the repeated attempts at impeachment have brought both the President's and Congressional approval ratings to unprecedented depths. Only 39% of respondents approve of President Clinton, according to a NewsSource/InternetCo survey last week, a record low -- but still 22 points higher than Congressional approval. As is common in these surveys, approval for the respondents' own Representative and Senator averaged much higher, at 48%.

Adding to Clinton's woes is the rising popularity of Trump News, a cable and Internet channel providing "real news, not fake news" with an extreme conservative tilt. With well-known Fox News personalities Sean Hannity and Tucker Carlson already in prime time slots, Trump News recently announced that it would be hiring former Fox commentator Bill O'Reilly. O'Reilly had been dropped by Fox after multiple sexual harassment accusations.

Trump News, started by GOP presidential candidate Donald Trump immediately after his narrow loss to Clinton in 2016, has largely taken over for Fox News as the voice of conservative politics in America. Trump himself provides a nightly commentary. Coupled with his Twitter stream, he remains a constant presence in the American political landscape.

The prominence of Trump infuriates many Clinton supporters, who point to evidence that the Russian government aided the Trump campaign and sought to sow chaos in the 2016 election. Attorney General Jamie Gorelick authorized an investigation of the Russian effort, but there has been little public attention to the still-ongoing inquiry. Republican officials, when asked about evidence of a Russian attempt to hack the voting process, refer to President Clinton as a "sore winner" seeking explanations for her "unexpectedly poor showing."

Many of Clinton's opponents take this further, claiming -- without evidence -- that millions of illegal and fraudulent votes pushed her to victory, an idea endorsed by Mr. Trump. Multiple efforts to force a recount of votes in Wisconsin, where President Clinton saw her narrowest victory, failed to trigger an official reconsideration of that state's outcome.

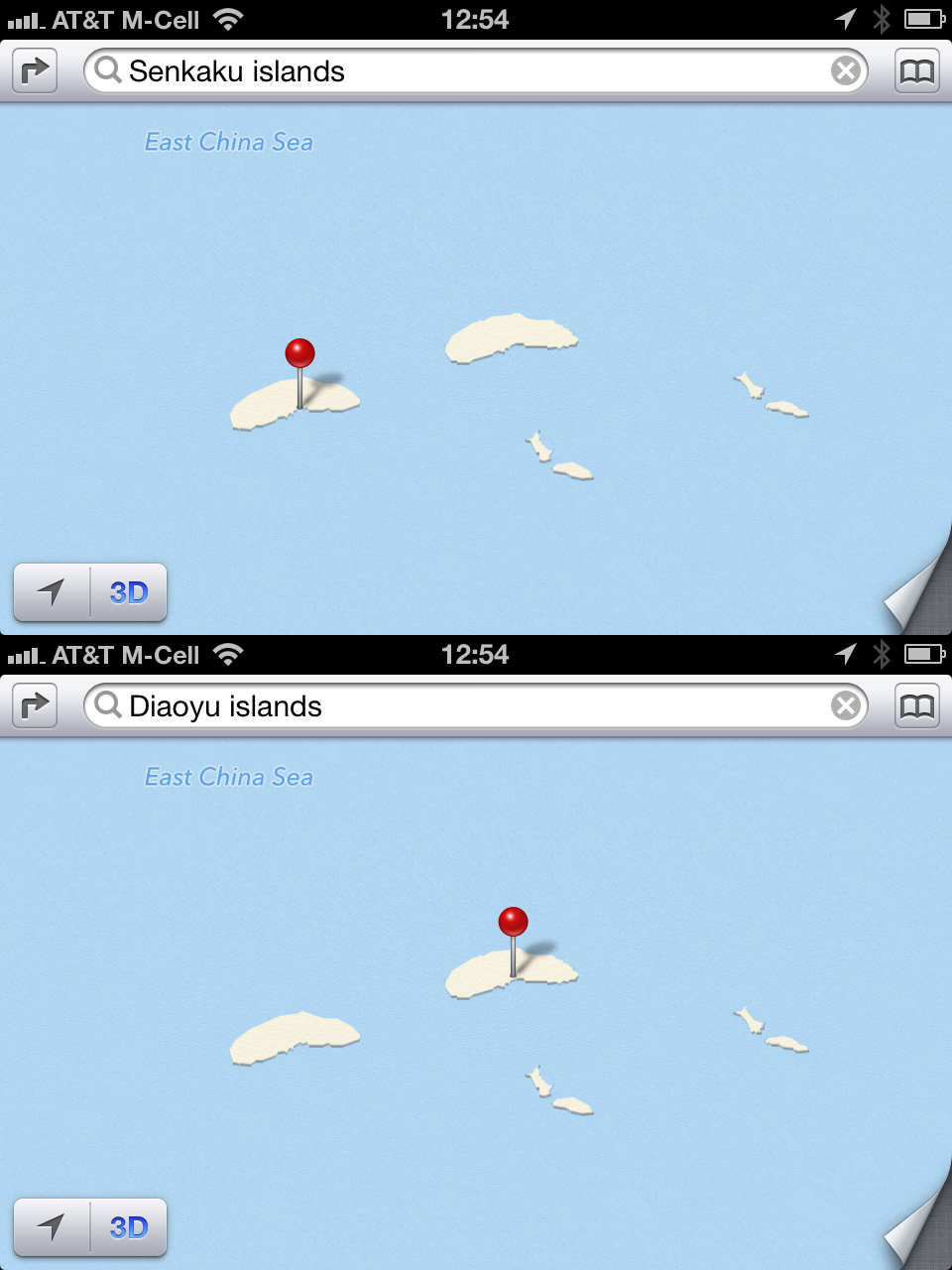

With the domestic political environment showing no signs of improving, President Clinton has focused her attention on foreign policy. Diplomatic experts have praised her handling of relations with China, the ongoing nuclear threat from North Korea, and the diminishing threat of ISIS, but the tragedy of the Syrian civil war refuses to relinquish center stage.

Most observers say that resignation would be unlikely, but the fact that President Clinton's team is giving this option serious consideration shows how untenable her situation has become.

The only other President to resign, Richard Nixon, did so under the cloud of imminent impeachment and likely conviction.

Clinton's successor as Secretary of State under Obama, John Kerry, put it this way: "I don't want to say that the circumstances are hopeless... but they are starting to look hopeless."

Plague, Inc., by

Plague, Inc., by

Bear with me -- this is going to get twisted.

Bear with me -- this is going to get twisted. One of the fundamental jobs of a futurist is to keep an eye out for the tentative signs of emerging changes -- sometimes referred to as "early indicators" or as "

One of the fundamental jobs of a futurist is to keep an eye out for the tentative signs of emerging changes -- sometimes referred to as "early indicators" or as "

My new Fast Company article went live this morning, "

My new Fast Company article went live this morning, "

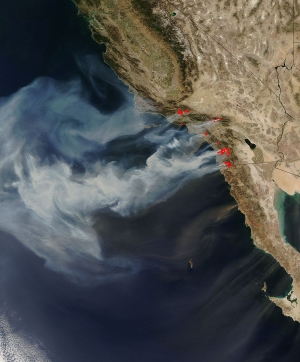

Climate Chaos and... Ubiquitous Transparency

Climate Chaos and... Ubiquitous Transparency

Geoengineering -- or, as I sometimes call it, re-terraforming the Earth -- is back in the news, with a

Geoengineering -- or, as I sometimes call it, re-terraforming the Earth -- is back in the news, with a  My arrival in Budapest yesterday afternoon was largely uneventful*, and today's my first full day in the city. Already, however, I can see what the primary theme of the visit will be: transition.

My arrival in Budapest yesterday afternoon was largely uneventful*, and today's my first full day in the city. Already, however, I can see what the primary theme of the visit will be: transition.

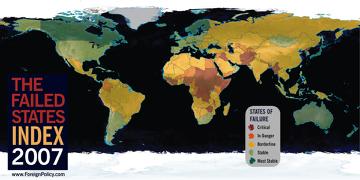

Foreign Policy magazine has come out with its annual listing of "Failed States. Perhaps not surprisingly, most of the media attention to this list has

Foreign Policy magazine has come out with its annual listing of "Failed States. Perhaps not surprisingly, most of the media attention to this list has  When American voters go to the polls next Tuesday, nearly 40% will encounter a so-called Direct Recording Electronic (DRE) voting machine, usually referred to as a touch-screen voting machine, and another 40% will encounter optical scan voting machines. The security risks involved in the current model of electronic voting are so abundant and so varied that it's almost too big of a problem to consider, but Jon "Hannibal" Stokes at Ars Technica has produced a

When American voters go to the polls next Tuesday, nearly 40% will encounter a so-called Direct Recording Electronic (DRE) voting machine, usually referred to as a touch-screen voting machine, and another 40% will encounter optical scan voting machines. The security risks involved in the current model of electronic voting are so abundant and so varied that it's almost too big of a problem to consider, but Jon "Hannibal" Stokes at Ars Technica has produced a  An Agence France-Presse article, reprinted at Terradaily.com, got me thinking about some of the unanticipated results of a radical shift to renewable energy systems.

An Agence France-Presse article, reprinted at Terradaily.com, got me thinking about some of the unanticipated results of a radical shift to renewable energy systems.