It seemed a little thing, at first.

It seemed a little thing, at first.

“Hey, let’s start a blog.” I don’t know whether it was Alex Steffen or I who said it first (he was always more proactive, I was always more techie), and it undoubtedly wasn’t said in those exact words, but still. Alex had been living in the SF region for a short while, back in 2003, and neither of us had a real job. We’d known each other for close to a decade at that point, but had never really done a big project together.

The way I remember it, we had initially imagined that the blog would be something to work on while we figured out what we really wanted to do. Kinda future-y, kinda green-y, a place to kick around ideas before putting them in front of a “real” audience. A place to write without worrying about deadlines or last-minute editorial fiats.

Some of the ideas behind Worldchanging were worked out as Alex put together what ended up being the last issue of Whole Earth magazine. We bounced arguments off each other, and the lengthy essay I wrote for the issue ended up articulating a perspective on the world that, at its root, I still hold. Alex assembled an amazing set of contributing writers, and the issue was all set to rock. But it never saw print, because the foundation behind the magazine decided that the funding just wasn’t there. We started Worldchanging, in part, to get past that — to have a place to write that wouldn’t be yanked away at the very last minute because somebody ran out of money. (As the saying goes, irony can be pretty ironic sometimes.)

But even before Worldchanging really got started, we could sense that we were onto something big. There’s an electricity that comes from seeing the zeitgeist form in front of you. The core idea of Worldchanging — that the world’s a mess, but it doesn’t get fixed by just complaining about it, so let’s focus on what will make it better — made immediate sense, and everyone we told about what we were going to do got excited at the prospect. We knew that we had to do it. Worldchanging didn’t just seem to be a good idea, it seemed to be a necessary idea.

For us, this necessity wasn’t just a belief, it was visceral reality. In our pre-Worldchanging work, Alex and I had each independently stumbled across a surprising and troubling truth. Few, if any, of the organizations we’d worked with as consultants (on business strategy, on environmental strategy, on their own futures) could articulate a plausible positive scenario. They couldn’t imagine what the world would look like if they were successful, only what might happen if they failed. They didn’t have the language with which to describe a realistic world that worked. We knew that had to change.

With the clarity of hindsight, the scale of the task we had made for ourselves was rather daunting. We were trying to transform how we — as a world — saw the world, to create a paradigm that was at once grounded in deep traditions and eager to innovate, to start a revolution. We knew that we couldn’t do it alone, but we could damn sure try to be one of the sparks that set it off.

And we did.

We weren’t the only ones who saw the zeitgeist, but for a time we were the ones who had figured out how to say what needed to be said in ways that people wanted to hear. The language and the arguments we used went quickly from being niche perspectives to being cornerstone ideas of a new (or revitalized, take your pick) view of a sustainable, resilient, desirable world. Over time, with great effort and generous contributions of time and money from hundreds of people, we fought our revolution... and won.

Not in the sense that the ideals that Worldchanging embraced are now universally accepted, or that the goals we fought for have been accomplished, of course. Rather, we won in the sense that the Worldchanging perspective — that complaints aren’t enough, that we need to focus on solutions, that a better world isn’t just possible, it’s here if we want it — is now widely seen to be as obvious and necessary as Alex and I saw it back in 2003. For the Worldchanging concept, spectacular visibility wasn’t the real goal; what we wanted was invisible ubiquity.

So when I get word that Worldchanging has ended its run, I don’t see it as a sign of failure, not by any means. Instead, it’s a recognition of success, that the efforts and contributions paid off. Ultimately, if Worldchanging no longer offered a unique voice, it wasn’t because Worldchanging had lost its way — it was because Worldchanging’s voice had become a global chorus.

Yep, pretty busy lately. I hope to have a book announcement soon, though.

Yep, pretty busy lately. I hope to have a book announcement soon, though.

This has already been a busy year, and it's just getting more hectic.

This has already been a busy year, and it's just getting more hectic.

It seemed a little thing, at first.

It seemed a little thing, at first.

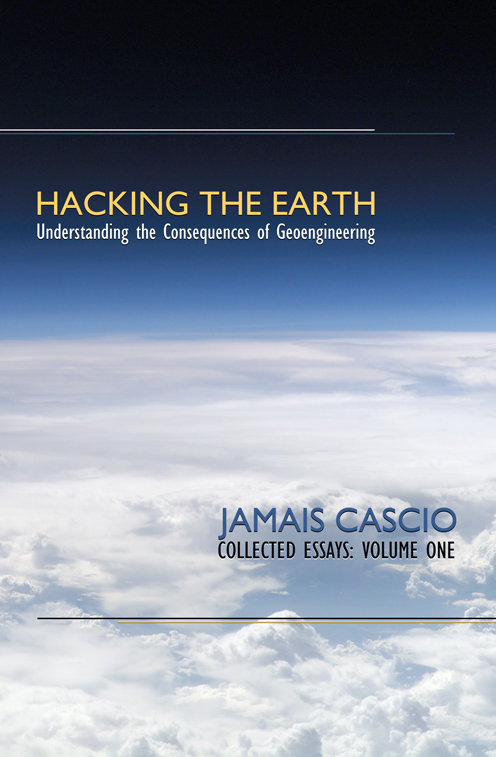

My publish-on-demand book on geoengineering, Hacking the Earth, has been picked up on Amazon.com. This is happy-making for a couple of reasons. The first is that this means people who have heard about the book and go looking for it on the world's biggest online bookseller (what a crazy idea) now will find it. The second is that it means that I could do a Kindle version quite easily. So here you go:

My publish-on-demand book on geoengineering, Hacking the Earth, has been picked up on Amazon.com. This is happy-making for a couple of reasons. The first is that this means people who have heard about the book and go looking for it on the world's biggest online bookseller (what a crazy idea) now will find it. The second is that it means that I could do a Kindle version quite easily. So here you go:

Press Release

Press Release

Given that the folks at the Takeaway Festival weren't recording the talks for posterity, I didn't expect to see how the Skype-video presentation I did on Wednesday turned out. It turns out, though, that British designer

Given that the folks at the Takeaway Festival weren't recording the talks for posterity, I didn't expect to see how the Skype-video presentation I did on Wednesday turned out. It turns out, though, that British designer  This is a busy week (aren't they all), but with some unusual events thrown in:

This is a busy week (aren't they all), but with some unusual events thrown in:

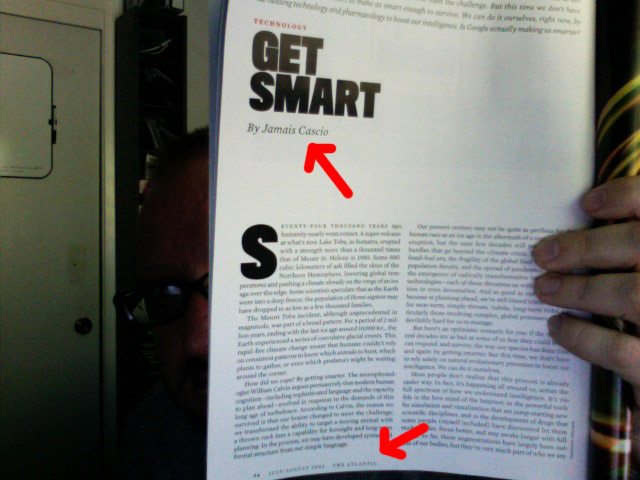

Trinity College Professor of Healthy Policy

Trinity College Professor of Healthy Policy  Air travel is the persistent dilemma facing a climate-conscious consultant. Plane flights are particularly nasty sources of greenhouse gases, in part because of the direct emissions, and in part because of where the gases are emitted. One round-trip between San Francisco and London

Air travel is the persistent dilemma facing a climate-conscious consultant. Plane flights are particularly nasty sources of greenhouse gases, in part because of the direct emissions, and in part because of where the gases are emitted. One round-trip between San Francisco and London

My good friend and colleague

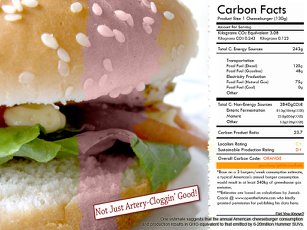

My good friend and colleague  The Cheeseburger Steamroller continues, as I show up on Treehugger radio (playing online and on Air America) talking about the cheeseburger footprint story. The conversation is actually excerpted from a much longer description of how and why I undertook this investigation. The folks at TH tell me that they're going to put that longer audio clip up either later today or tomorrow.

The Cheeseburger Steamroller continues, as I show up on Treehugger radio (playing online and on Air America) talking about the cheeseburger footprint story. The conversation is actually excerpted from a much longer description of how and why I undertook this investigation. The folks at TH tell me that they're going to put that longer audio clip up either later today or tomorrow.

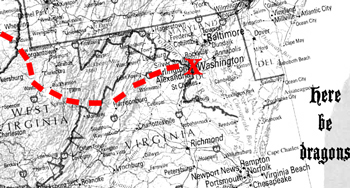

I will be heading to Washington, DC, in a couple of weeks, ostensibly to take part in a short workshop for the Institute for the Future. I'll be coming in a few days early, however, in order to hit a few of the sights (and to spend some time with a good friend). I'll be arriving late on Saturday, December 2nd, and will have free time available for most of Sunday and Monday.

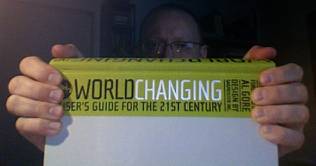

I will be heading to Washington, DC, in a couple of weeks, ostensibly to take part in a short workshop for the Institute for the Future. I'll be coming in a few days early, however, in order to hit a few of the sights (and to spend some time with a good friend). I'll be arriving late on Saturday, December 2nd, and will have free time available for most of Sunday and Monday. Well, my contributor's copy of the WorldChanging book --

Well, my contributor's copy of the WorldChanging book --

The life of a consulting futurist can be trying. Take next week, for example: I'll be flying off to Honolulu for five days, a guest of the

The life of a consulting futurist can be trying. Take next week, for example: I'll be flying off to Honolulu for five days, a guest of the