This happened a couple of years ago, but I was just reminded of it again recently (and it didn't receive the attention it deserves).

This happened a couple of years ago, but I was just reminded of it again recently (and it didn't receive the attention it deserves).

The story of the Guiding Hand Social Club and the Valentine Operative offers one scenario of how advanced griefing functions: it zeroes in on trust and community.

EVE Online is one of those lesser-known massively-multiplayer online role-playing games that scurries in the shadow of World of Warcraft. It's a science fiction game, wherein you fly around the galaxy fighting pirates and shipping goods, tricking out your successive generations of starships. The game itself is free, with a 30-day free trial (like nearly all other MMORPGs, ongoing play requires a subscription). The game developers update the universe on a regular basis, and the tens of thousands of players seem to enjoy the game quite a bit. (Incidentally, EVE has an on-staff economist to help them shape the game world, adding to its complexity.)

There's one other bit of information about EVE that's important to know: you can (and probably will) fight other players. It's not a safe universe out there.

The Guiding Hand Social Club (GHSC) is a "corporation" in EVE -- a player organization that, in another game, would be called a "guild." GHSC bills itself as a group of mercenaries, willing and able to go after other corporations, stealing ships and cargo, for a (hefty) fee. In 2004, GHSC was hired (by a still-anonymous client) to attack the corporation Ubiqua Seraph and kill its leader, Mirial. But GHSC took the contract a bit further than expected -- after ten months of infiltration, a galaxy-wide coordinated attack netted billions in in-game money (worth approximately $16,500 in real-world money at the time), stole dozens of ships and other hardware, and destroyed Ubiqua Seraph's "Navy Apocalypse" flagship. GHSC operative Arenis Xemdal pulled the trigger on Mirial, after having risen in Ubiqua Seraph's ranks and reportedly developing a relationship with the target CEO.

"Arenis Xemdal is what we call a Valentine Operative." [GHSC leader] Shogaatsu explains. "Essentially his job is to seduce and entice an objective into a state of trust and confidence. As such, we'd call Mirial's relationship to him moments before the strike... 'endeared'."

The entire story is worth reading, and if you're particularly fascinated, the GHSC announcement of the strike remains on the EVE message boards. All in all, it's a remarkable story of coordinated treachery, malicious intent, and griefing severe enough to drive people out of the game.

But what does this have to do with the real world?

It's tempting to look at the GHSC strike in financial terms, focusing on the loss of money. But to me, the monetary theft aspect was secondary; the real point of the action was to make the target, and her comrades, miserable. In this, GHSC was eminently successful:

They claim this was a "kill contract" to destroy the player Mirial.....

While they did destroy her Navy Apoc and pod her.... they went beyond that.

They stole everything from UQS Billions of isk [the EVE currency] that dozens of players have spent over a year building up.. seriusly [sic] hurting many players feelings and causing emotional stress outside the game... (I'm not gonna die over it... but my mind shouldn't be taken up by game thoughts like this has caused)

Why is this different than past Corp thefts?????

THEY BRAGGED ABOUT IT......

(Emphasis mine.)

People who don't spend time in immersive digital worlds may not realize just how emotionally intense they can be. These are often games, yes, but they are built to enable visceral reactions akin to those arising from real-world experiences: danger, exultation, fear, anger, humiliation and sometimes even "endearment." And the more that 3D immersive worlds blend with the physical world, the more intense these emotional cues will be.

In the comments to yesterday's post, my friend J. Eric Townsend argues that there's little real difference between griefing and "hacking" (in the commonplace sense) -- viruses and malware written not to steal, but simply to be perversely destructive. I see his point. Like most griefers, the "skr1pt k1dd13s" and virus-makers so prominent in the early days of the web had little motivation other than attacking other computer user for the fun of it.

But there is a difference, and it's a big one. While hacking and malware can destroy data and one's sense of security, griefing goes after trust and social cohesion. The teammate who shoots me instead of the opposing team isn't just attacking my datastream, he's attacking me. The prevalence of malware on the Internet seems environmental, like some kind of biohazard -- the origin of a virus or scam may be useful for the digital epidemiologists, but what I care most about is making sure my immunities are up to date. There are no such protections from griefing, because its presence depends on the social behavior we value in the participatory web. You can eliminate griefing by eliminating social interaction; it becomes necessary to destroy the town in order to save it.

And here we have the dilemma of the blended era. The appeal of social technologies, immersive technologies, is their extraordinary capacity to link us together, to build resilient and complex communities out of little more than thought and light. But those same luminous pathways enable malice of startling power. We built the metaverse and social web as ancillary networks, parallel to (but less meaningful than) our physical world communities. That pairing has quickly reversed itself, however, and the digital links have become -- for a rapidly growing number of us -- the primary social bond. But the norms and ethics of online life haven't evolved as rapidly, leaving us in a moment of transition: we are enraptured with the power of connection and painfully surprised by it at the same time.

Blizzard Entertainment, the game company behind hits like Starcraft and World of Warcraft, just announced the details of its (relatively) soon-to-be released game, Diablo III. The original Diablo and Diablo II were big hits, and although D2 came out in the late 1990s, it still sells in numbers high enough to make annual top ten sales lists in 2010. Millions of people still play Diablo II on the "Battle.net" multiplayer servers, and millions more likely still play in solo mode. It's likely that D3 will be the biggest hit of whatever year it ends up coming out in, simply out of pent-up anticipation. It's no exaggeration to say that tens millions of people will likely play Diablo III on a regular basis.

Blizzard Entertainment, the game company behind hits like Starcraft and World of Warcraft, just announced the details of its (relatively) soon-to-be released game, Diablo III. The original Diablo and Diablo II were big hits, and although D2 came out in the late 1990s, it still sells in numbers high enough to make annual top ten sales lists in 2010. Millions of people still play Diablo II on the "Battle.net" multiplayer servers, and millions more likely still play in solo mode. It's likely that D3 will be the biggest hit of whatever year it ends up coming out in, simply out of pent-up anticipation. It's no exaggeration to say that tens millions of people will likely play Diablo III on a regular basis.

The

The  I wrote about the "

I wrote about the " Good googly-moogly. Just as it seemed to be settling down, the Internet drama about Xeni at

Good googly-moogly. Just as it seemed to be settling down, the Internet drama about Xeni at

My talk at the Stanford Metaverse Meetup on November 27 is now available as a video.

My talk at the Stanford Metaverse Meetup on November 27 is now available as a video.

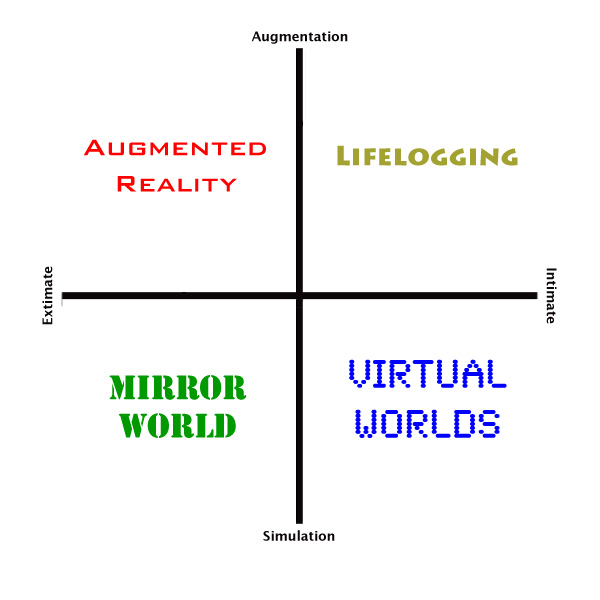

After months of work, the Metaverse Roadmap Overview is now available for download;

After months of work, the Metaverse Roadmap Overview is now available for download;  Tonight, Microsoft announced its new "

Tonight, Microsoft announced its new "

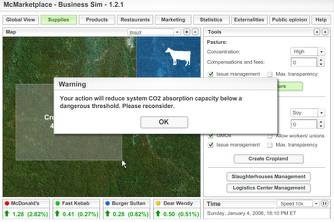

Never underestimate the power of a "do-over."

Never underestimate the power of a "do-over." Ah, only if this were real...

Ah, only if this were real... I've been fascinated for many years by the emergence of virtual worlds. Their attractiveness is obvious to anyone who has read a work of fiction and imagined themselves in that world, either alongside the heroes or off exploring new spaces. Paper and dice role-playing games (such as D&D or

I've been fascinated for many years by the emergence of virtual worlds. Their attractiveness is obvious to anyone who has read a work of fiction and imagined themselves in that world, either alongside the heroes or off exploring new spaces. Paper and dice role-playing games (such as D&D or